Writing for The Dispatch late last year, Yuval Levin offered a compelling diagnosis of a paradoxical pathology infecting modern life. For the past two decades, there has been a sharp decline in symptoms of social disorder—such as divorce, abortion, and (until perhaps recently) crime—that plagued the latter half of the twentieth century. But accompanying them in their retreat have been many of the positive indicators of a healthy and vibrant society: marriages, births, homeownership levels, friendships, and even lifespans. The successful pruning of the unbridled passions that drove social dysfunction in our parents’ generation seems to have masked or even partly fomented a withering of a different sort in our own. “There is less social disorder, we might say, because there is less social life,” Levin observes. “We are doing less of everything together, so that what we do is a little more tidy and controlled.”

Levin lays part of the blame on the financial difficulties that make it tough for young people to reach traditional markers of adulthood. But he also faults a culture of “excessive risk aversion” that is “intertwined with a more general tendency toward inhibition and constriction.” Unconvinced by the poorly translated social scripts that once guided their ancestors, yet lacking meaningful alternatives, the generations of the digital age are trapped in a paranoid state of existential indecision—one exacerbated by a sense of social, economic, and ecological precariousness.

But what if constriction of a different sort is precisely what bewildered millennials and Gen Zers need? In many ways, that is the argument of David McPherson’s The Virtues of Limits and Pete Davis’s Dedicated: The Case for Commitment in an Age of Infinite Browsing, two excellent new books on the value of the circumscribed life. McPherson is an associate professor of philosophy at Creighton University who writes with a conservative sensibility, while Davis is the co-founder of the Democracy Policy Network and a civic activist, with decidedly more liberal commitments.

In spite of their differences in background and disposition, these authors pursue a shared mission. Both McPherson and Davis reject utopian promises of society’s perfectibility in favor of working within the borders of a broken world. Both root their arguments among a rich discursive lineage of thinkers and actors. Most importantly, both authors speak a shared language of cultivation: of finding a home in the world through the life-giving nurture of the bounded and the particular.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Why We Should Embrace Limits

In The Virtues of Limits, McPherson makes two distinct but intertwined arguments. On the one hand, the book is a defense of four kinds of contextual boundaries: existential limits, moral limits, political limits, and economic limits. On the other, it is also an argument for the role that “limiting virtues” play in setting these boundaries and guiding the good life. Venturing beyond the cardinal virtues of classical ethics, McPherson delineates humility, reverence, moderation, contentment, neighborliness, and loyalty as six spheres of moral excellence all too overlooked today.

Out of these six, McPherson elevates “humility” as “the master limiting virtue.” That is because humility is the key to adopting what he describes as an “accepting-appreciating” stance to moral existence, one that is in direct opposition to the protean promises of our age. Instead of embracing the given, McPherson argues that we moderns are too quick to adopt what he calls a “choosing-controlling” posture, which uses our dissatisfaction with our material and moral conditions to fuel ever-frenzied attempts to bend the world to our desires (and augments our despair when those attempts are thwarted).

McPherson furthermore posits that it is the “accepting-appreciating” stance, rather than its “choosing-controlling” antipode, that should reign supreme in our moral calculus. This is a challenging idea, one that sets McPherson apart from ethicists who instead reach for a kind of Aristotelian mean between these two countervailing attitudes. How on earth is it possible to accept and appreciate a world that is rife with so much pain, rotting under the weight of incurable diseases, corrupt leaders, fractured families, and exploited landscapes? The idea that acceptance should be the primary lens through which we mediate our actions invites the disconcerting possibility that we may fail to act in the name of goodness at all.

Properly ordering acceptance, choice, appreciation, and control allows us to take better stock of what one can reasonably accomplish in our individual circumstances. Moreover, it allows us to uncover the idiosyncratic beauty and joy that thrive within the confines of our limitations.

However, McPherson clarifies that it is not necessary to abandon a “choosing-controlling” stance entirely. It is rather a secondary mode that must also be guided by the limiting virtue of reverence, “a heightened form of respect” that demands appropriate responsiveness to objects that are reverence-worthy (such as human life).

This corollary makes McPherson’s Tao of acceptance and appreciation especially relevant to millennials and Gen Zers. These generations have been subjected to decades of social messaging that the good life is predicated on fostering unbounded dreams, reaching for ever-towering heights of achievement, and “changing the world.” Properly ordering acceptance, choice, appreciation, and control allows us to take better stock of what we can reasonably accomplish in our individual circumstances. Moreover, it allows us to uncover the idiosyncratic beauty and joy that thrive within the confines of our limitations.

While humility and reverence are at the heart of McPherson’s study of existential and moral limits (which includes a thoughtful interrogation of the virtues of absolute prohibitions), the other limiting virtues shine in his chapters on political and economic limits. For example, McPherson uses the virtue of neighborliness, which “recognizes the moral significance of proximity,” to construct a powerful case against Nussbaumian cosmopolitanism and a defense of “humane localism” as a foundational political principle. The virtue of contentment, or “knowing when enough is enough, of . . . not wanting more than is needed for a good life,” undergirds both an argument for a sufficientarian concept of economic justice and a sharp critique of the damaging effects of concentrated wealth and growing income inequality.

McPherson concludes his book with an encouragement to embrace Sabbath practices, in emulation of the day when God “completes his creation through appreciating it.” Even for those who are not religious, McPherson posits that rest plays an essential role in moral life. Just as music is partly defined by the silence between notes, moments of leisure allow us to better understand our world and where we fit in it. When our social media feeds are lined with carefully curated tableaus of diversion that are really designed for a kind of blind consumption, the exhortation to behold—to really see, and therefore to know—is precisely the challenge we need.

Choosing Commitment

McPherson’s The Virtue of Limits expresses a theory of the constrained life; Davis’s Dedicated explores what it looks like in practice. Although he got his start in the business world as the founder of an Instagram-friendly cabin rental service, Davis gained prominence as a public intellectual through a viral commencement speech he delivered at Harvard in 2018 on the “counterculture of commitment.” In Davis’s estimation, the crisis facing young people today is a prevailing cultural ethos that privileges flexibility and keeping options open over making choices. If life is a door-lined chamber, too many people are lingering in the hallway instead of turning a knob.

Davis elaborates on this thesis in Dedicated by looking at “long-haul heroes” who eschew casual relationships, short-lived job contracts, and city-hopping for investment in projects, places, and people. Like McPherson’s six limiting virtues, these countercultural “rebels” come in six forms: citizens, patriots, builders, stewards, artisans, and companions. Using a wide range of both modern and historical examples, Davis illustrates how citizens diligently drive worthy political causes forward and patriots express their love of country through service to their hometowns; how stewards and companions furnish the glue that holds institutions, communities, and families together; how builders and artisans create spaces and artifacts that communicate durability by being forged through tradition and dedication. Even as they differ in their scope, these archetypes all share the key understanding that a meaningful life is not defined by a few decisive moments of individual accomplishment—“slaying the dragon,” as Davis puts it. Instead, a meaningful life emerges out of the daily and faithful toil that, brick by boring brick, builds a bulwark against the dragons of “everyday boredom and distraction and uncertainty that threaten sustained commitment.”

Yet the emulation of any of these six “rebels” demands a choice, and Davis does not quite succeed in articulating a strategy for determining which model is the most appropriate use of our time and talents. He gestures to a somewhat confused matrix of “emotions, values, and rationality”—a pro and con list here, a bit of Ignatian discernment there—which in the end is supposed to lead us to “that spark of life that makes a choice feel right.” But what happens when we haven’t received the kind of formation needed to help us separate what makes us feel good from what is best for us (and therefore more conducive to true happiness)? What happens when our gut itself is disordered?

Davis’s language about “feeling right” sounds an odd note against his more incisive point that commitment is a painful exercise, that each decision involves a certain degree of spiritual “mutilation” as we smother or even sever pieces of ourselves that don’t quite serve the roles we pledge to perform. “When we associate with something, we have to deal with the full chaos that comes with it,” Davis explains. “You associate with something because you like parts of it, but nobody likes all the parts of it.” To a certain extent, commitment requires a loss of control, which can be a terrifying prospect to those who have been told incessantly that their generation’s sole inheritance is instability (a chorus that may also explain the allure of the meticulously manicured “personal brand”). But the sacrifice that commitment demands bears an important gift: a sense of purpose that inoculates us from existential despair by giving definition and solidity to our lives. As Davis concludes, “it is only in turning away from ourselves that we can discover who we are.”

If Davis struggles with some inconsistency in his argument, it is only out of an attempt to widen the breadth of his message’s appeal. He rightly has no patience, however, with figures on the right who think that the answer to our modern ennui is an Arcadian return to “involuntary commitments” and “rigid hierarchies,” nor with those on the left who silo themselves into increasingly esoteric and exclusionary subcultures masquerading as forms of activism. These voices represent an approach to commitment that is ultimately impoverished by a sterilizing sense of certainty. A commitment is a leap of faith that we take with those we commit to, where the only guarantee is that we will all be transformed.

The sacrifice that commitment demands bears an important gift: a sense of purpose that inoculates us from existential despair by giving definition and solidity to our lives.

Tending the Garden

The language of limits and choices can be a tough sell for individuals who feel like they have had no options. This is undoubtedly true for those who are most disadvantaged in our society, who still lack the financial and social supports needed to secure some purchase worth constraining. It is also worth remembering that on a world-historical scale, the opportunity for marginalized groups such as women and minorities to exercise choice beyond a suffocating set of social strictures is a treasured and recent phenomenon.

Yet a salutary flourishing of options has not been accompanied by the kinds of policies that facilitate the assumption of duties and loyalties, such as a robust safety net and working accommodations for families, or healthcare and job security for individuals with skills that do not conform to the information economy. Boomers and Gen Xers may bemoan friendship loss and demographic decline as much as they like, but they have yet to enact the kind of sensible, ostensibly bipartisan legislation that would counteract many of the forces driving the contraction of our social life. That Sen. Mitt Romney’s ingenious childcare proposal went nowhere fast is as sure a sign as any that the cavalry is not coming anytime soon.

Many of us have more choices than we may want to acknowledge. We can make a stand against the chaos and vapidity of our world by delineating a small corner of it that will demand our care and attention.

But that doesn’t mean that millennials and Gen Zers can let themselves off the hook. Many of us have more choices than we may want to acknowledge. We can make a stand against the chaos and vapidity of our world by delineating a small corner of it that will demand our care and attention. Drawing on McPherson’s accepting-appreciating stance and Davis’s case for commitment, we can embrace the kind of choices that limit yet enrich our existence. We can accept a less glamorous job that lets us live closer to our community of origin, give a date a second chance instead scrolling back through Tinder, volunteer with a local organization instead of squandering one more second fighting on Twitter, or reconsider the possibility of having a child (or one more than originally planned).

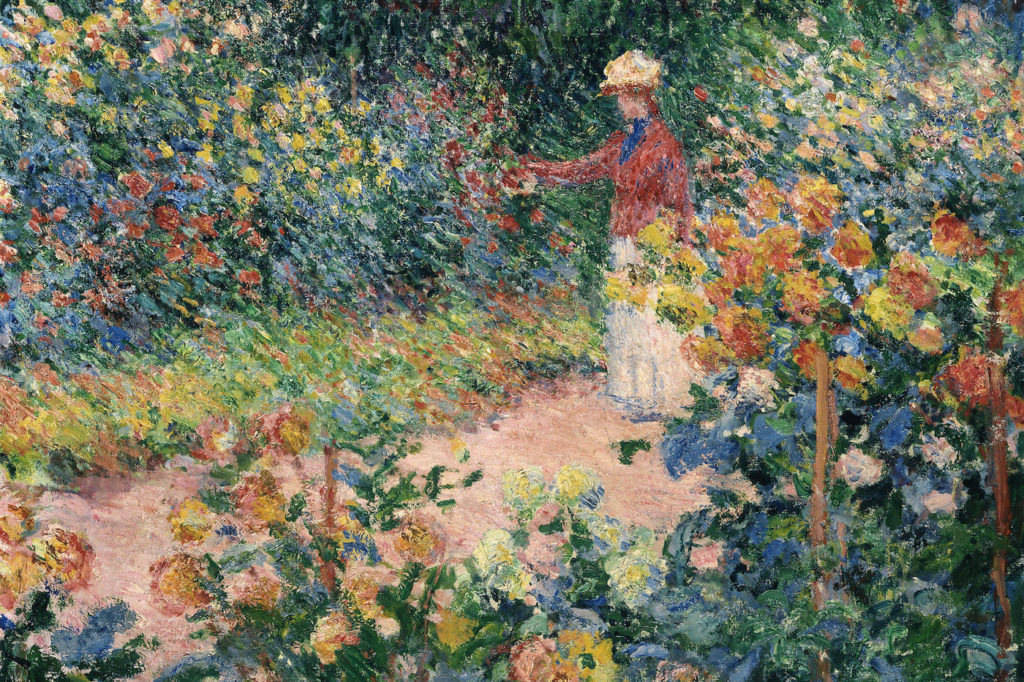

The image of gardening is a quiet undercurrent in both McPherson’s book and Davis’s for a reason. Gardening is an act of co-creation, requiring an appreciation of the quality of the environment, the vagaries of the weather, and the limitations of the very seeds themselves (one can hardly ask a violet to bear tomatoes, or an orange tree to sprout in the middle of a snowstorm). That gardens blossom at all is a function of unhistoric acts, and their fruits are often enjoyed by only a small sliver of our loud and bustling world. But to paraphrase George Eliot’s paean to limitations, it is so largely thanks to unhistoric acts that things are not so ill with you, me, and the countless gardens that compose our social landscape.