During his decades-long correspondence with John Adams, Thomas Jefferson did something that seemed quite out of character for an enthusiastic disciple of republicanism: issue praise of aristocracy. But this aristocracy was decidedly unlike George III’s increasingly tyrannical rule. Responding to two of Adams’s letters, Jefferson contrasted an “artificial aristocracy” founded on “wealth and birth, without either virtue or talents” with a “natural aristocracy,” which he described as “the most precious gift of nature for the instruction, the trusts, and government of society.” He continued with a provocative thought: “May we not even say that that form of government is the best which provides the most effectually for a pure selection of these natural aristoi into the offices of government?”

Centuries later, the political philosopher Harry V. Jaffa (1918–2015) argued that Jefferson’s understanding of aristocracy was a clear implication of our nation’s founding charter. “Democracy, understood from the principles of the Declaration of Independence,” he reasoned, “is not only consistent with aristocracy, it is aristocracy.”

For Jaffa, the self-evident truth that “all men are created equal” supplied the proper foundation for those with self-mastery and other well-developed virtues to rule. The enlightened consent of equal citizens through elections could elevate statesmen with unequal wisdom to the highest offices in the land. Rather than leveling all distinctions, he contended that by linking consent to wisdom, the Founders’ doctrine of equality produced a just inequality. As James Madison wrote in Federalist 10, protecting the diverse “faculties of men . . . is the first object of government.”

In The Soul of Politics: Harry V. Jaffa and the Fight for America, Glenn Ellmers’s purpose is to make our elite class great again. Through a deep exploration of Jaffa’s scholarship, he aims to rouse the “spirited moral gentlemen” of our times to meet the challenge of “the crisis of Western civilization.” He calls on citizens of prudence, virtue, and foresight to eschew despair and cynicism and rise to their nation’s defense at a time of great need.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.For Jaffa, the self-evident truth that “all men are created equal” supplied the proper foundation for those with self-mastery and other well-developed virtues to rule.

Nihilism and Dogmatic Skepticism

A Senior Fellow at the Claremont Institute, Ellmers argues that historicism and relativism have culminated in a destructive nihilism that is bent on tearing down every vestige of America’s past. Lawlessness and mob rule have threatened vast swaths of the country. As the “uniparty establishment” fiddled in 2020, sections of major American cities—including Minneapolis, Atlanta, Chicago, San Francisco, Portland, and St. Louis—burned. Mobs tore down statues of Americans and non-Americans indiscriminately. A curriculum influenced by the mendacious 1619 Project, which itself is based on pernicious concepts derived from critical theory, is being taught in our nation’s classrooms.

None of this would have surprised Jaffa, who saw these threats to republican government in embryonic form decades earlier. As most Americans were celebrating the fall of Soviet communism, in a 1990 essay he noted the existence of an “unprecedented threat to the survival of biblical religion,” “autonomous human reason,” and “political freedom.” He pointed to two main culprits: a dogmatic skepticism of any permanent standards of nature outside the human will and a politicized conception of science brandished by apparatchiks in the bureaucracy.

Jaffa taught generations of students—first at Ohio State University and then at his long-time home at Claremont McKenna College—to reject a fatalistic acceptance of the West’s decline. Through Talmudic studies of Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas, Shakespeare, America’s founding documents, and Abraham Lincoln’s speeches, Jaffa brought philosophic insight to bear on questions of country, patriotism, and statesmanship. Years of studying at the feet of Leo Strauss, a German emigré who revived the study of classical political philosophy in the twentieth century, led him to see philosophy’s usefulness for maintaining the American regime.

Ellmers writes that Jaffa “promoted an explicitly political and practically focused application of classical political philosophy.” Though Aristotle taught that the intellectual and moral virtues were distinct—the contemplative life of the philosopher versus the active life of the statesman—there is nevertheless some overlap between them. Political philosophy doesn’t simply stay in the heavens. Rightly understood, it seeks to understand and enlighten the pre-philosophic opinions of citizens. Ellmers argues that this includes providing for the education of the gentlemen and maximizing “their influence in the world.” The practical end of political philosophy is to encourage statesmen to found or make an existing regime the best possible one in this world.

Political philosophy doesn’t simply stay in the heavens. Rightly understood, it seeks to understand and enlighten the pre-philosophic opinions of citizens.

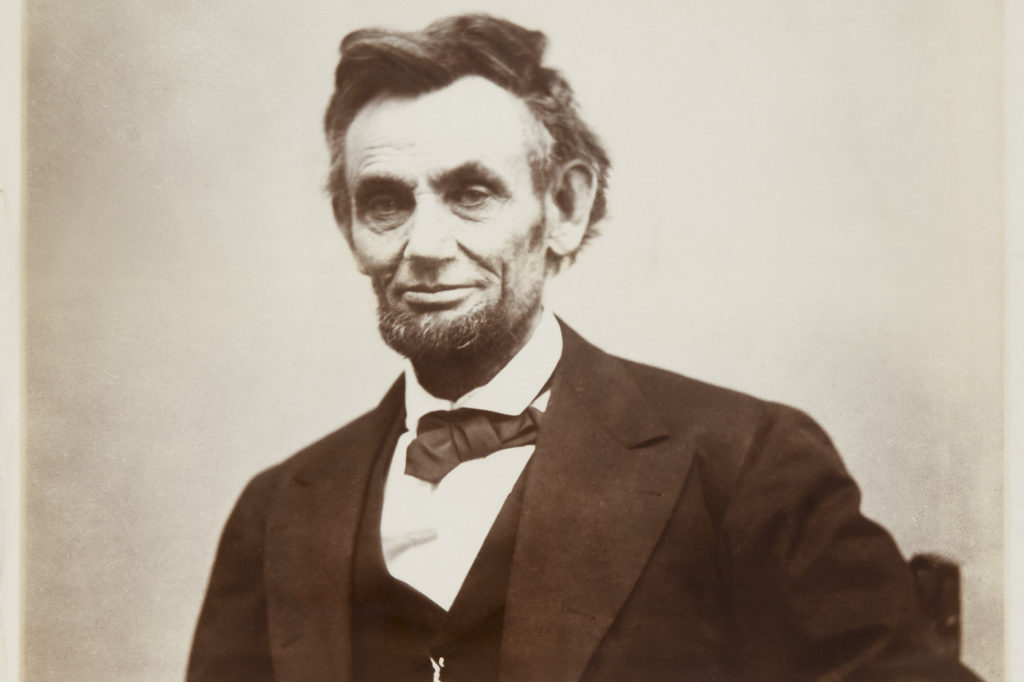

Lincoln: The Template for Statesmanship

Jaffa applied these insights to America through a close study of Lincoln in two pathbreaking books: Crisis of the House Divided: An Interpretation of the Issues in the Lincoln-Douglas Debates and A New Birth of Freedom: Abraham Lincoln and the Coming of the Civil War. While studying Plato’s Republic with Strauss, Jaffa realized that the arguments of Socrates and Thrasymachus on justice were identical to the arguments Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas made in their famous series of debates in 1858. Douglas resurrected Thrasymachus’s argument that justice was “in the interest of the stronger.” By contrast, Lincoln looked to the principles of the American founding—especially the truth of natural human equality—to deal with the problem of slavery. Rather than transcending the Founding, a position Jaffa had advanced in Crisis, Lincoln called “the American people back to their ‘ancient faith’” through the common language of Shakespeare and the King James Bible.

Lincoln’s invocation of common references and biblical imagery and allusions showed Jaffa that the proper use of rhetoric was a crucial aspect of statesmanship. Rather than make a machine-gun listing of facts, Lincoln demonstrated that a prudent combination of logos, ethos, and pathos was required to sway audiences to his position. He channeled the people’s feelings, passions, and sentiments toward the causes of keeping the union together and, eventually, of slavery’s “ultimate extinction.” To his generations of students, Jaffa mirrored Lincoln’s rhetorical range. He wove together insights from classical and modern philosophy, literature, and the Bible to explain and defend America. For his intellectual opponents, however, he tended to lean on one specific strategy: unleashing torrents of thumos.

Reclaiming Americanism

A boxer when he was young, Jaffa was fond of quoting the aphorism solet Aristoteles quaerere pugnam (“Aristotle is accustomed to seeking a fight”). He relished fights in print with intellectuals such as Irving Kristol, Martin Diamond, and Harvey C. Mansfield, and with conservative legal titans including Robert Bork, Ed Meese, and Antonin Scalia. He believed his colleagues in the academy misunderstood the character of the American Founding, and most judges had wrongly rejected the Constitution’s natural law foundations. Ellmers acknowledges that Jaffa was sometimes too vehement in his denunciations and could be slow to express gratitude for his interlocutors. Nevertheless, he helped guide the Right—National Review founder William F. Buckley is one of many examples—to a more American understanding of the nation’s principles, traditions, and history.

Jaffa saw the American founding as the best example of prudential statesmanship in the modern world.

Ellmers notes that Jaffa’s regular skirmishes with Willmoore Kendall, a paleoconservative thinker and professor of political philosophy, led him to “a deeper appreciation of how natural right must always be adapted to a particular regime, to a people with a particular character.” (Though a critic of the paleocons, Ellmers writes approvingly that their “emphasis on grounding political life in a particular people with concrete religious and cultural habits” is “an important and necessary part of” a republican way of life.)

Classical political philosophers like Plato and Aristotle saw natural right as a permanent standard of justice that was always true no matter the calendar year. Jaffa understood that “the means of implementing” natural right, however, “must follow the dictates of prudence, taking into consideration circumstances that are not universal, but particular.” Prudence “encompasses the entire range of possible human action,” he argued, “and is therefore the guiding principle of the most comprehensive human community, the political regime.” Quite simply, “Prudence is the virtue par excellence of the statesman.”

Jaffa saw the American Founding as the best example of prudential statesmanship in the modern world. Describing the Founders as “one of the most exceptional generations of political men who ever lived,” he noted that they were “morally and politically wise men, the kind of characters from whom Aristotle himself drew his portraits of the moral and political virtues.” They understood that a prudential politics comprehends both form and matter—political theory and the character of a people. As Alexander Hamilton once wrote, “a government must be fitted to a nation as much as a Coat to the Individual, and consequently that what may be good at Philadelphia may be bad at Paris and ridiculous at Petersburgh.”

The Theological-Political Problem

For Jaffa, the central aspect of the Founders’ statesmanship was solving the theological-political problem, which had plagued politics since the dawn of Christianity. The authority of the laws of the ancient city was tied to its particular gods, but the God of Israel, who first revealed Himself to a specific people, then announced Himself as the God of all people. (“There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus” [Galatians 3:28].) The law’s authority had to be re-established in a monotheistic world in which citizens had a dual allegiance to the city on earth and the city in Heaven.

Where the divine right of kings failed, Jaffa taught that the Declaration’s appeal to the “laws of Nature and of Nature God” succeeded. By preserving “the coexistence of the claims of reason and of revelation,” which, Leo Strauss stated, supplied the “secret vitality of the West,” the Founding safeguarded both the civil and spiritual kingdoms. Thomas G. West, a student of Jaffa’s, succinctly summed up this idea: by eliminating the “salvation of the soul as an end of politics,” the Founding elevated “political life” by removing “a leading source of its degradation—namely, persecution arising from the conviction of one’s own sanctity.”

Despite disagreement on the “ends served by the moral virtues,” Jaffa argued that reason and revelation were in “fundamental agreement on a moral code which can guide human life both privately and publicly.” Both taught the importance of the family and private property, the problematic nature of deciding sectarian issues through politics, and the wrongness of keeping humans perpetually in bondage. As Rev. Samuel Cooper said during a 1780 election sermon, “We want not, indeed, a special revelation from heaven to teach us that men are born equal and free; that no man has a natural claim of dominion over his neighbours, nor one nation any such claim upon another.”

Rather than a collection of atomized individuals who looked to pursue their own private pleasure, Jaffa saw the American regime as being founded on a “true partnership” of citizens “in pursuit of the good life.”

American Civic Virtue

Pointing to a myriad of documents from the Founding period, Jaffa viewed the American Founding in light of high virtue, not low self-interested hedonism. He saw that the Founders’ political theory was firmly set on the foundations of natural right and natural law. As evidence for this position, he regularly quoted Washington’s teaching from his First Inaugural that “there exists in the economy and course of nature an indissoluble union between virtue and happiness.” Reflecting on this truth, Jaffa wrote, “Republican citizens must exercise restraint, industry, and self-respect in order to be responsible, first for themselves and then for their families and communities.”

For the Founders, liberty was not license; rights and duties were alternate sides of the same coin. Rather than a collection of atomized individuals who looked to pursue their own private pleasure, Jaffa saw the American regime as being founded on a “true partnership” of citizens “in pursuit of the good life.” (He pointedly noted in a letter to Norman Podhoretz that he “loathed Hayek’s philosophical libertarianism as much as I loathe the socialism he taught me to despise.”)

Ellmers concludes his book by contending that “the exercise of prudence” is “now and always the soul of politics.” Today, prudence demands setting aside political strategies that were created to meet the challenges of different times. It means rejecting political quietism and defeatism in favor of forming coalitions and networks, building parallel institutions, and wielding political power on behalf of the public good. We would be wise to reflect on and act in light of Ellmers’s patient and illuminating look at Harry Jaffa’s scholarship, because nothing less than the future of our nation is at stake.