To discover more excellent reads and cinema selections, don’t miss our Isolation Bookshelf collection.

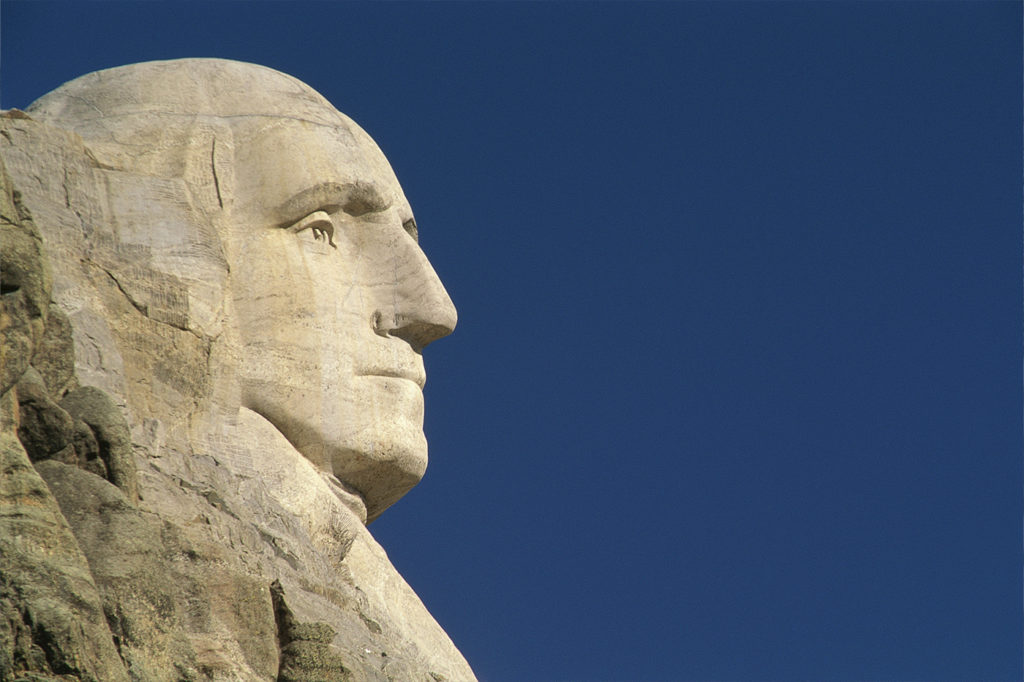

In many parts of our country, a thoughtless, convulsive form of iconoclasm seems to have come over many of our fellow citizens. Statues of Columbus and Grant are toppled, George Washington has paint splashed on him in New York’s Washington Square, and even the “removal” of Mt. Rushmore has been called for. The nation’s recent focus on matters of racial justice has brought a welcome attention, in my opinion, to the propriety of Confederate symbols on state flags, of Confederate statues in public spaces (about which I have written here at Public Discourse), and of naming military bases after officers in the Confederate army. But attacks on Washington and Grant, on Columbus, and even on a depiction of Lincoln emancipating a slave, bespeak an inability to think clearly about why we honor people with statues and monuments.

Attacks on Washington and Grant, on Columbus, and even on a depiction of Lincoln emancipating a slave, bespeak an inability to think clearly about why we honor people with statues and monuments.

While the Trump era has spawned a lot of discourse on the virtues and vices of “nationalism,” I think what we could use more of is patriotism. Lincoln remarked at Gettysburg that the United States had been, since its founding on July 4, 1776, dedicated to a proposition, a set of self-evident truths stated in the Declaration of Independence. This means that American patriotism, properly understood, has never been the reflexive support of “my country right or wrong,” but instead has always been the reflective, self-critical posture “my country because it is dedicated to the right.” This requires that we continually work to maintain and improve the justice of our country. Americans love America because it is their own and because it is good. Our ability to detach ourselves from America and decry its injustices only increases our attachment to it as a continuing project that is truly our own.

No one thought more deeply on this subject than the late Walter Berns, in his 2001 book Making Patriots. Berns understood the peculiar merging of particularism and universalism that characterizes the American love of country: “Ours is not a parochial patriotism; precisely because it comprises an attachment to principles that are universal, we cannot be indifferent to the welfare of others. To be indifferent, especially to the rights of others, would be un-American.” And this conviction of ours about rights forges the strongest possible bond of citizens to their country: “Would Americans have fought for the Union—and 359,528 of them died fighting for it—if they had been taught in their schools that the Union was founded on nothing more than an opinion concerning human nature and the rights affixed to it? Not likely; but fight they did, and for that we honor them.”

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Berns’s little book, one of the last he published in a long and distinguished scholarly career, was a labor of gratitude, and a work that responded to a felt necessity, as he saw thoughtful patriotism was on the wane. A similar motive animated Norman Podhoretz in My Love Affair With America: The Cautionary Tale of a Cheerful Conservative (2000). Not uncharacteristically for Podhoretz, there is a combative tone and at times a relish for score-settling in this book. But it’s a lovely self-portrait of how a little Jewish son of immigrants, who was marched off to remedial speech class at the age of five thanks to his strong Yiddish accent, could look back in gratitude on the teachers who made an American of him. Falling in love as well with the English language and with great literature, Podhoretz learned to love America more steadily and deeply as he studied at Cambridge, served in the army, and embarked on a long career as a writer and editor at Commentary magazine during the tumultuous 1950s and ’60s, when patriotism came under siege. Reflecting at the end of this book on the American founders’ devotion to liberty, he writes: “For this we, who are their posterity, either by blood or by adoption, should be giving daily thanks.”

If you say, this Fourth of July, “happy Independence Day,” pause for a moment and breathe your thanks to George Washington for it.

Gratitude, as well as probing intellect, characterizes another book worth mentioning. This year is the sixtieth anniversary of the publication of John Courtney Murray’s We Hold These Truths: Catholic Reflections on the American Proposition, a book that made such a splash in 1960 that its author, a Jesuit priest, landed on the cover of Time magazine that December. (The election of America’s first Catholic president probably helped.) My late friend Peter Lawler, in his introduction to a 2005 reprint of the book, described Murray as “one of America’s very few genuine political philosophers.” Concerning the book’s present reputation, Peter continued:

It is praised by liberals for paving the way for Vatican II’s embrace of the American idea of religious liberty, and it is blamed by conservatives and traditionalists for obscuring the real conflicts between Catholicism and “Americanism.” Both the liberal praise and the conservative blame are somewhat misguided. The last thing Murray wanted to do is bring the church up to date with the latest currents in American thought. He wanted to show how distinctively Catholic thought could illuminate the authentic American idea of liberty.

The memorable takeaway from Murray’s account of the American founders is that they “built better than they knew.” This is a judgment that has come in for unjust mockery from time to time. And in an age when the founders are knocked for being villains, failures, and hypocrites, it is good to read an account that takes them seriously as flawed human beings who really did build something solid, sound, and upward-looking.

This Independence Day, perhaps we could reacquaint ourselves with those flawed but truly heroic human beings. How fragile and precarious was the founding moment is a lesson that comes through in David McCullough’s 1776 (2005), a narrative of the pivotal year in the war for American independence when Boston was regained and New York was lost, when George Washington’s Continental Army retreated through New Jersey and finished the year with the famous Christmas victory at Trenton. Readers who recall the mellifluous voice of McCullough from Ken Burns’s Civil War documentary will be pleased to know the author reads the audiobook version of 1776 himself.

On the subject of George Washington, we might learn something from a man who knew him and fought under him. John Marshall, when he was chief justice of the United States, authored a five-volume Life of George Washington, which he later revised into a two-volume work, and finally condensed into a one-volume “school edition.” That single-volume version is in print today from Liberty Fund, and as I remarked in an appreciation of it last year, Marshall depicts a general with “unconquerable firmness,” without whom we would probably not have a country at all. As president, Washington was to display the same indomitable character. He was a man incapable of demagoguery, impossible to frighten into precipitous decisions, resistant to mere impulses, and ever mindful of his responsibility for setting the course of his country’s future. He was indeed first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen. And he deserves, to this day, every honor a grateful country can bestow on him.

If you say, this Fourth of July, “happy Independence Day,” pause for a moment and breathe your thanks to George Washington for it.