A couple months ago, a friend (of Heather’s) posted on Facebook: “With June being pride month and everything, I decided that I wanted to update everyone on the recent big point of my life. First of all, many of you don’t know, but I am pansexual. Along with that I am polyamorous, and I am currently in a triad with two wonderful people who make me incredibly happy.” After Heather reached out to her in an effort to understand, she said, “My boyfriend and I were in a relationship and then he introduced to me his long-time girlfriend and everything clicked. So now she’s our girlfriend. For our [the triad’s] relationship to work, it’s like any other relationship. We have to communicate.”

This type of relationship is commonly referred to as consensual non-monogamy (CNM). A CNM relationship is an umbrella term for polyamory and various kinds of sexually open relationships. This means that more than two individuals are in a relationship, with all partners consenting to each other’s participation in the relationship, including all additional emotional and sexual connections. A recent study found that nearly 3 percent of U.S. adults are currently in an open sexual relationship, with 12 percent of adults reported to be in an open sexual relationship at some point in their lives. Millennials and Gen Xers are a little more involved with and supportive of CNM than the Silent and Baby Boom generations.

A polyamorous connection, for example, might look like one in a recent New York Times photo essay, where married couple Beth and Andrew Sparksfire are shown lying next to another couple. Next to Andrew is his girlfriend, Effy Blue, with her boyfriend, Thomas Kavanaugh. Beth and Thomas, however, are not in a relationship with each other. They all say consensual non-monogamy works for them. But would it work for more than just a few? And while some may think this practice leads to more gender equality, does it?

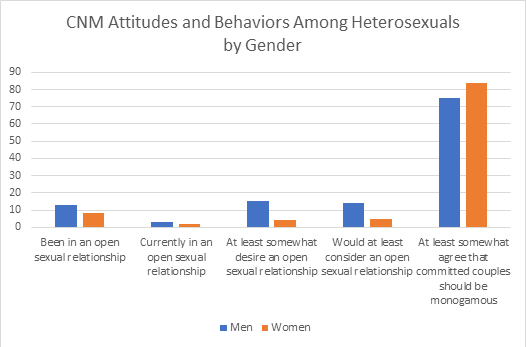

A recent study from the Wheatley Institution and the School of Family Life at Brigham Young University (the iFidelity Survey) provides some insight into this question. The nationally representative survey showed clear differences between adult males and females in their willingness to participate in and give consent to a CNM relationship. As shown in the table below, heterosexual men desired an open sexual relationship almost four times more than their female counterparts: 15 percent versus 4 percent. (However, note that it is still a small proportion of men who express approval.) Men also were almost three times more likely than women even to consider an open sexual relationship: 14 percent versus 5 percent. These data suggest another front in the battle of the sexes—at least in their comfort level or desire for a CNM relationship.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.So, why might women be generally less willing to participate in a CNM relationship? Perhaps women, on average, prioritize an emotional connection that comes from exclusivity with their partner more than men do. As one female college student said, “I would not be interested [in CNM]. If I’m dating someone, I wouldn’t want to worry about if he’s with someone else. . . . I would just keep getting hurt.” While there is large variation among women in their sex drive, men on average tend to have a higher sex drive than females. This could result in some men’s desire to have consensual opportunities for more sex, more variety, and more partners.

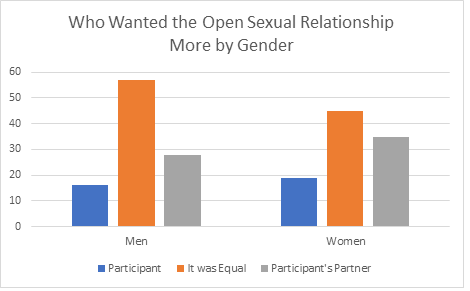

In further analyses of the iFidelity Survey, the desire for a CNM relationship showed starker differences between men and women. In this analysis, only those survey respondents who had ever been in a CNM relationship were analyzed (246 survey respondents). Only about half the time was their desire for an open relationship mutual or equal. More than a third (35 percent) of women who had been in an open relationship said their male partner wanted the open relationship more, while more than a quarter (28 percent) of men said their female partner wanted the relationship more. Note too that there was more than a 10-percentage-point difference between males and females in their reports that the CNM relationship was equally desired (57 percent versus 45 percent). The data suggest that we should be more skeptical about the term “consensual” in consensual non-monogamy and challenge the idea that these kinds of relationships lead to greater gender equality rather than less.

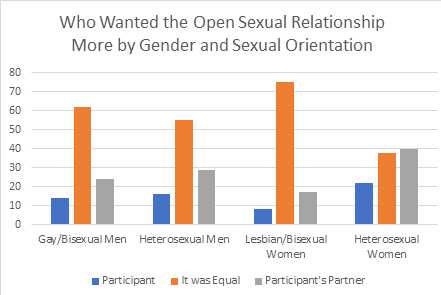

What if we include responses by individuals with other sexual orientations? An interesting story emerges when you separate the findings by both sexual orientation and gender. Males, regardless of sexual orientation, were fairly similar in reporting who wanted the CNM relationship more: 50 to 60 percent reported that the decision was equal (with 20 to 30 percent reporting their partner wanted it more).

The story is different for females, however. Females who identified as lesbian/bisexual reported the desire for a CNM relationship to be equal 75 percent of the time. However, only 38 percent of heterosexual women reported the CNM relationship to be equally desired. And heterosexual women were much more likely—23 percentage points more likely—to report that their male partner wanted the open relationship more. When including sexual orientation in the equation, we still see some important differences between men and women. And importantly, we see some gender inequality favoring men in heterosexual CNM relationships.

So, the question remains: How “consensual” is consensual non-monogamy?

What if one partner holds more leverage because she or he makes more money, is more attractive, or is better at initiating new relationships? Can full consent be given when partners are in unequal positions? Does an unemployed, introverted homemaker, dependent on a financially successful, extroverted, and sexually adventurous spouse, really have much power not to consent when her or his partner asks for an open relationship? The standard response is that open communication between partners is the key to resolving this situation. But is honesty sufficient in situations where one spouse has greater power and leverage than the other?

Furthermore, do the challenges of making a relationship work dissolve simply by giving willing permission? For instance, for many individuals in CNM relationships, jealousy still predictably rears its head. According to Janet Hardy, author of The Ethical Slut, who is in a polyamorous relationship herself: “We [polyamorous individuals] are humans, and anybody who has raised children or dogs knows that envy and jealousy are built into the wiring, but the difference I think in CNM is that we know jealousy will come up, and we have a commitment to survive it. . . . [W]e work out techniques for dealing with it.” Jealousy, not always a welcome emotion, gets added to the list of emotions to expect in this arrangement.

Granted, there is a lot of talk in CNM circles about “compersion,” a feeling of joy seeing a partner happy in a sexual relationship with someone else. Most, however, will not react with glee to their romantic partners’ sexual ecstasy and emotional connection with some other romantic partner. For those who prefer to avoid jealousy rather than to work hard to manage it, maybe working to keep the spark alive with their one-and-only should be the first priority. Many couples are able to keep the passion alive year after year. Could this monogamous “constraint” actually lead to more joy and more freedom? And ultimately more satisfying love? And will growing acceptance and practice of CNM subtract from efforts to create greater gender equality?