Father Wilson D. Miscamble, C.S.C.’s, excellent biography of Father Theodore Hesburgh, American Priest, shows a man of great faith and great ambition whose life’s work was to make Notre Dame a “great Catholic university.” Under his leadership, Notre Dame attained the academic excellence and prestige that Father Hesburgh sought, and in the process changed the face of Catholic higher education. Father Miscamble’s book throws light on the man at the center of this transformation, the price paid, and some of the reasons why Catholic identity is tenuous in Catholic universities today.

Father Hesburgh’s life is an all-American story and a deeply Catholic one. It was a central belief of Father Hesburgh that these two core facets of his character were compatible. And it is the tensions between those facets that later developed that serve as the animating theme of Father Miscamble’s biography of the man he warmly calls Father Ted.

All-American Catholic

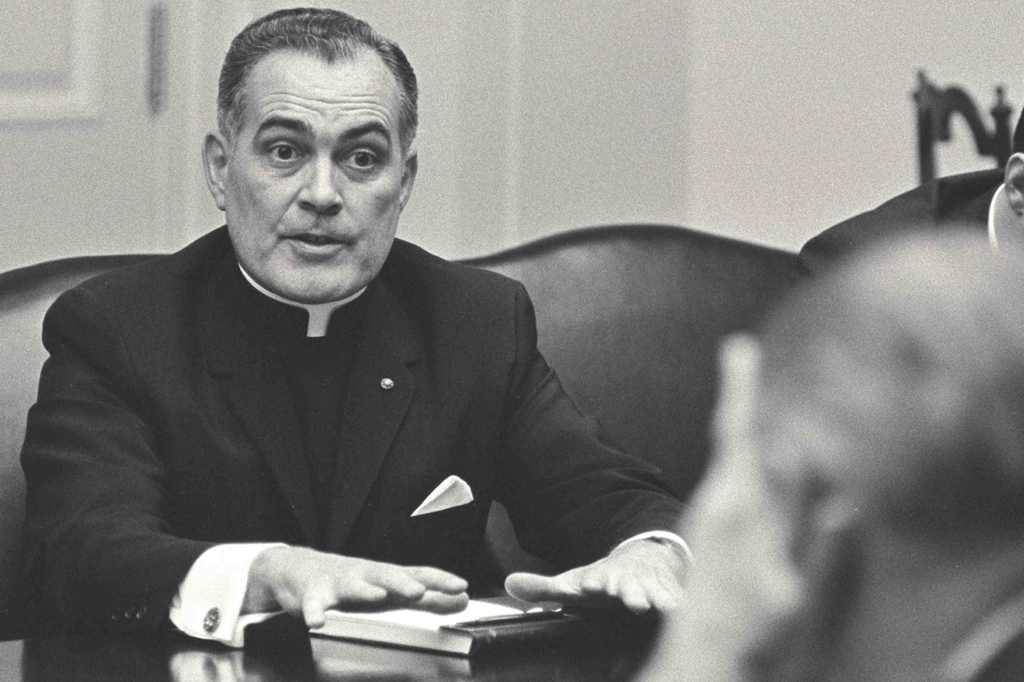

The story that Father Miscamble tells is an all-American story—the rise of a Catholic of relatively modest background, close to his immigrant roots, to a place of prominence among the nation’s elite—a man who conferred with presidents and popes. Theodore Hesburgh was born in 1917 into “a vibrant Catholic subculture, rather typical of the period, that centered” on the family’s parish and school in upstate New York. His religious formation was also typical for the era, including a “solid grounding . . . in Scholastic philosophy and orthodox theology.” This background deeply informed the worldview that Father Ted brought to his work as president of Notre Dame and in public service. He carried a deep love of both his country and his Catholic faith. And although he later perceived that the United States had not fully lived up to her own ideals, especially with respect to the treatment of racial minorities, he saw no contradiction between these two loves.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.It is unclear whether someone like Father Ted could rise so high in today’s America—in part because the subculture of American Catholicism in which he was raised no longer exists, and in part because of the culture-wars that have gripped the country since the late 1960s. Hesburgh was born and reared in an American Catholic Church that worked hard to show that Catholics not only fit into American society, but that faithful Catholics were actually the best of citizens. He carried this American-Catholic ideal with him throughout his life, a point reflected in the title of his autobiography, God, Country, Notre Dame. This was no mere ideal: Father Miscamble’s story of Father Ted’s life shows the extent to which it was practically realizable.

As Father Miscamble makes clear, it was in part a deliberate avoidance of the most socially divisive issues (where the Church’s message is especially needed to counter the ethos shared by many elites) that enabled Father Ted to stay in the good company of the powerful men with whom he had become friends. For instance, although he served on the Rockefeller Foundation and was close friends with Nelson Rockefeller and his brothers, Father Ted failed to voice objection to their support for population control. “In essence he acquiesced in the substantial continued support that the Rockefeller Foundation gave to groups like the Population Council and the Planned Parenthood Federation of America.” He merely “abstain[ed] from voting on issues involving contraception, sterilization, and abortion.” Although Father Ted stood up for civil rights (appearing with Dr. King and serving on the U.S. Civil Rights Commission) and spoke out against the Vietnam War (somewhat late in the game, after the Tet Offensive), he “failed to make abortion and the right to life one of the great issues that he chose to address forcefully.”

Catholic Higher Education

Of greater importance than the issues Father Ted did or did not champion are the changes he brought to Notre Dame and Catholic higher education. He was the driving force behind the 1967 Land O’Lakes Statement, a kind of “declaration of independence” signed by leading Catholic educators that famously declared that a “Catholic university must have a true autonomy and academic freedom in the face of authority of whatever kind, lay or clerical, external to the academic community itself.” To realize this autonomy from clerical authority, Father Ted led the way in separating the University from the Holy Cross order that founded Notre Dame by vesting practical ownership and control of the institution in a new lay board of trustees. This served as a model that most Catholic colleges and universities soon replicated. While Land O’Lakes also said that Catholicism must be “perceptibly present and effectively operative” in a Catholic college or university, it offered no explicit, practical means for realizing this presence beyond hosting a theology department and campus ministry program. In addition to theology and campus ministry, which he enthusiastically supported, Father Ted saw the experience of community as an essential feature in the education of students at a Catholic university, and so he “robustly defended” a residential hall system based on single-sex dorms.

Father Miscamble’s biography shows that “[b]uilding Notre Dame into a ‘great Catholic University’ was always [Father Ted’s] central mission,” but that Hesburgh failed to achieve this goal by his own standards. Father Ted’s vision of a “great Catholic university” required the pursuit of “excellence” as defined by the secular academy, and while the details of this vision “were not clear,” he knew it meant “breaking free from . . . [the] complacency and mediocrity” of the past.

In practice this meant abandoning Neo-Thomism as the organizing principle of the university’s intellectual life but with nothing to take its place. Unfortunately, Father Ted “gave little serious attention to fashioning a curriculum appropriate for a modern Catholic university and almost no consideration to the task of recruiting capable and committed faculty to teach it.” To the extent that Notre Dame has retained a more robust sense of Catholic identity than have its fellow Catholic universities, it is not because of Father Ted’s vision of “excellence,” but because Notre Dame followed to some extent the commonsense advice of then-Provost Rev. James Burtchaell, C.S.C.: the project of Catholic higher education cannot be sustained without a predominant number of Catholic intellectuals.

In sum, “[t]he ends were stated, but the means were not well addressed.” As a consequence, many faculty were hired “who primarily possessed academic credentials validated by secular peers.” Because it lacked the requisite personnel, Notre Dame in fact gave up on “any effort to provide students with a truly distinct and coherent Catholic education that would guarantee them some introduction to a Catholic worldview.” Thus, contrary to the popular view of Hesburgh as the great visionary of Catholic higher education, the conclusion to be drawn from Father Miscamble’s book is that Father Ted’s plan for the future of Notre Dame lacked the practical means necessary to realize the goal of a “great Catholic university.” Father Ted was right to try to take Notre Dame forward into the realm of elite institutions. But he was wrong to think that a university’s Catholic identity is something that would just take care of itself once the school had in place a theology department, an active campus ministry, and a sense of community in residential life.

Father Miscamble interviewed Hesburgh on numerous occasions in preparation for his book. We too were fortunate to interview Father Ted on a crisp February morning in 2012, in his office overlooking the Notre Dame campus on the top floor of the Hesburgh Library, named in his honor. Somewhat to our surprise, our conversation revealed a man who did not think of himself primarily as the builder of a great institution, but first and foremost as a priest of the Catholic Church. Father Ted spoke lovingly of the chance he had had to exercise his priestly ministry, celebrating the Eucharist in dozens of countries and on every continent on Earth, including Antarctica.

The purpose of our meeting was to gather information for our book on the history of Catholic legal education in the United States, for we knew that Father Ted had played a critical role in that story. Today, Notre Dame’s law school stands out among the nation’s twenty-nine Catholic law schools because it has retained a vibrant Catholic identity that is not merely ornamental, cultural, or liturgical, but one that is intellectual in nature. In our interview, Father Ted told us that he first became directly involved with the Law School when he was vice-president of the University under Rev. John Cavanaugh, C.S.C., who gave him the task of finding a new dean. Cavanaugh told him that Notre Dame had “a first-rate football team and a third-rate law school.” He wanted the Notre Dame Law School to be first-rate, and he wanted it to be Catholic. Father Ted completed his assignment by hiring Joseph O’Meara to serve as dean. Under O’Meara’s tenure, the school set forth on the long path toward national recognition. O’Meara and his successors—William Lawless, Tom Shaffer, David Link, Patti O’Hara, and Nell Newton—hired a majority of faculty who were not only excellent scholars and rigorous teachers, but individuals who sought to contribute to Notre Dame as a center of Catholic intellectual life. Indeed, the law school has succeeded by following a hiring strategy (the strategy recommended by Burtchaell) that most Catholic law schools and universities did not follow—a failure that accounts for the beige brand of Catholic identity that is a hallmark of Catholic higher education today.

Cultivating Catholic Identity

A deep irony runs throughout Father Miscamble’s biography. On the one hand, it is clear that Father Ted was a man of deep faith whose priestly vocation was the center of his being. Even in the aftermath of Vatican II, “Ted Hesburgh drank deeply of the well of this priestly understanding and spirituality.” On the other hand, Father Ted presided over the thinning of Notre Dame’s Catholic identity, primarily through his lack of attention to faculty hiring and curriculum. What can account for this puzzling combination of personal fidelity and the loss of a robust sense of Catholic identity in the institution that he oversaw?

Father Miscamble’s biography shows that Father Ted came of age in the thick American Catholic subculture that thrived during the 1920s-1950s. From that perspective, it was plausible to believe that Notre Dame’s faculty and curriculum would remain, not just nominally Catholic, but richly Catholic in its intellectual heart even as the university sought to engage with its secular peers and attain the excellence defined by the wider academy. However, Father Miscamble’s biography also shows that Father Ted’s assumptions were no longer warranted by the early 1970s. Catholics and America had changed. A Catholic university could no longer take for granted the deep Catholic enculturation achieved through the interlocking networks of family, parish, school, and social and charitable organizations that once defined the Catholic “ghetto.” Relocation to the suburbs, the selection of public over parochial schools, and the tragic loss of religious observance that followed in the wake of Vatican II all contributed to a loss of Catholic identity long before any faculty or students ever set foot on campus. This new environment required the university and its leaders to self-consciously cultivate a faculty of Catholic intellectuals and deliberately structure a curriculum with the goal of introducing students to a Catholic worldview. Father Ted did not recognize the loss that had occurred and failed to provide for it sufficiently.

The portrait of Father Theodore Hesburgh that emerges from Father Miscamble’s study is of a man who was a dedicated priest and a leader who possessed enormous ambition, charm, intelligence, and dedication—a man who realized the goal of making Notre Dame a great university, one respected among its secular peers. But for all his many gifts, Father Hesburgh lacked the vision and imagination necessary to realize the goal of making Notre Dame into a great Catholic university in the modern world.