This essay is part of our back-to-school series. See the full collection here.

In his 1987 book The Closing of the American Mind, the late Allan Bloom wrote of a debate he once had with a psychology professor when he taught at Cornell University. The psychologist “said that it was his function to get rid of prejudices in his students. He knocked them down like tenpins. I began to wonder what he replaced those prejudices with. He did not seem to have much of an idea of what the opposite of a prejudice might be.” Bloom continued:

I found myself responding to the professor of psychology that I personally tried to teach my students prejudices, since nowadays—with the general success of his method—they had learned to doubt beliefs even before they believed in anything. Without people like me, he would be out of business. . . One has to have the experience of really believing before one can have the thrill of liberation. So I proposed a division of labor in which I would help to grow the flowers in the field and he could mow them down.

After nearly four decades of teaching undergraduates myself, I am more convinced than ever that Bloom was on to something. His colleague in psychology apparently understood “prejudice” to mean “unfounded negative or ugly or self-serving opinion,” a mere synonym for “bigotry” or “chauvinism.” Bloom knew better; he knew that human beings can hardly get through the day without prejudices of all sorts—ingrained beliefs about the way things are, or ought to be, that go largely unexamined.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Some prejudices are good to have, some are bad, some are indifferent. Anyone can benefit from the discovery that one of his prejudices was a manifest error, a stupid misdirection in his attitude to the world and his fellow men. But acquiring an education is learning to discriminate the good prejudices one carries about from the bad ones—to keep the former, as confirmed by knowledge, and discard the latter, as condemned by knowledge. And the teacher who presumes to “get rid of” all the prejudices of his students has dedicated himself to attacking all their unexamined good beliefs as well as their bad ones.

Students who are just beginning their college careers should bear Bloom’s point in mind. The professor who is merely an iconoclast is not your friend, and not a teacher so much as a puerile provocateur. No doubt each of you has been formed and habituated to certain patterns of thought and belief by your parents and the rest of your family, by your teachers and other mentors, by your religious communities, by the mores of your neighborhood and your friends. None of you has been raised by wolves, and I dare say practically none of you among a pack of fools. It stands to reason that a great deal of what you think and believe—even or especially the most unreflected-upon things you believe—is intellectually and morally sound. Do not lightly give up any of this patrimony.

At Princeton University’s James Madison Program, where I work, we have “Some Thoughts and Advice for All Students” that I encourage you to read. It’s sound advice for students anywhere, at any school and in any field of study. The linchpin of the advice is “think for yourself.” Truth-seeking is undermined by “groupthink” and the “tyranny of public opinion.” At your age, of course, and in your circumstances, trying ideas on for size is the most natural thing in the world. And like our choices in clothes, our choices in ideas are affected by fashion. Unthinking attraction to what is fashionable is to be avoided. So is unthinking repulsion from the fashionable. Take your time, and work on figuring out what’s right and what’s wrong.

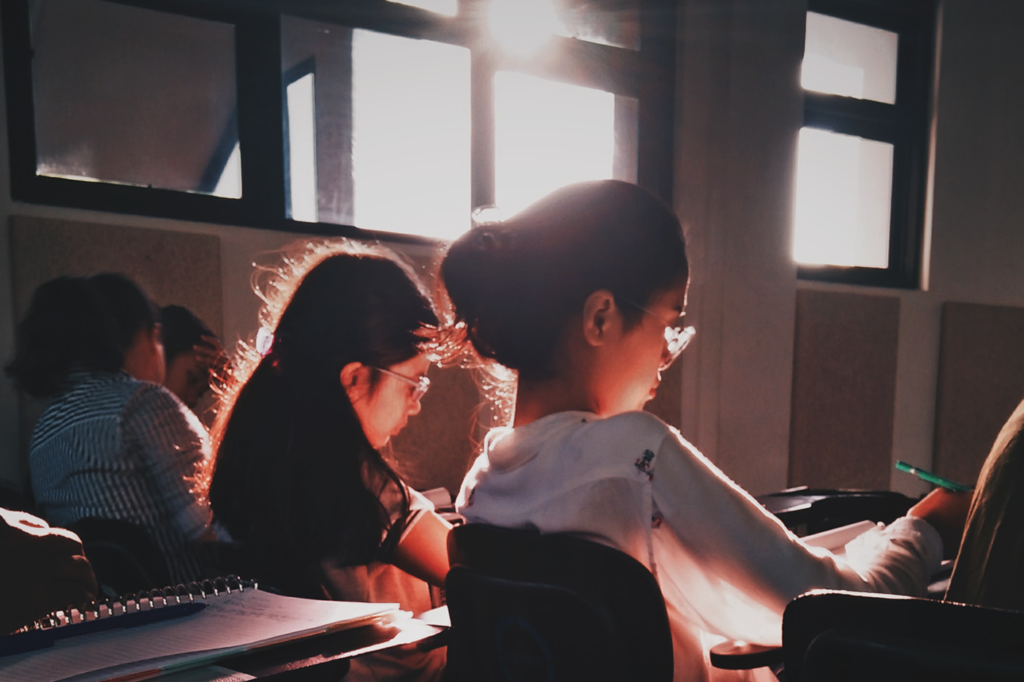

One of the unfortunate patterns of college orientation today, as the former dean of Yale Law School Anthony Kronman has observed, is that “extraordinarily talented young people, of every complexion and ethnic origin,” arrive on their campuses each fall and “are encouraged, even before they have begun to get their bearings, to think of themselves as members of a group, first, and individuals second. They are steered, by the culture of the school, toward the affinity groups that today define the balkanized terrain of college life.” We who welcome you to your college campus can do better, and we should. But those of you who encounter this herding of sheep according to the flocks they presumptively belong to should resist it, and find your own circles where you learn the best and have mutually supportive friends.

Much of the buzz of activity on college campuses, today as when I was a student in the 1970s, is generated by political activism. A passion for justice is a very good thing—and I assure you it is not the exclusive province of the young. But I have to agree with political scientist Elizabeth Corey, who writes:

Too often, activism distracts from the central activities of college life—studying, mentoring, practicing, writing, talking, and teaching. The problem is that activism implicitly prioritizes one mode of experience—the political—over others that are essential to liberal learning. Activism offers a powerful sense of solidarity with our like-minded comrades, but it also sharply divides us from those who do not share our views. It is a hindrance to friendship.

This is an important point, not least because friendship is one of the most important facets of the academic experience. It’s a cliché but a true one: you will probably make some very long-lasting, perhaps even lifelong, friendships while you are in college. And as Aristotle understood, the best sorts of friendships are those in which the friends regard one another’s good as truly their own. Not one another’s utility, not one another’s pleasure, not even one another’s comradeship in arms in some righteous cause, can encompass the complete good that one’s friend deserves from oneself. Only the shared devotion to knowing—and living the knowledge—of what the good life consists of can be said to constitute that friendship. Whatever is conducive to such friendship, in the classroom and out of it, is worth seeking. Whatever detracts from it is to be avoided or at least kept from dominating one’s waking hours.

Of course, another passion beckons the young soul finding itself liberated from parental authority on arriving to campus. I refer to romantic love, sexual longing—eros. It is hardly the place of the aging professor to give counsel to the ardor of youth. Allow me simply to say this: open your hearts but guard your virtue. Yes, “your virtue.” The modern college campus is full of traps and pitfalls where pain, heartache, and even worse miseries await you. In the #MeToo era, can this really be news? And the volatile cocktail of eros and alcohol—or other intoxicating substances—only makes the environment more dangerous.

So if you came to college as a practicing member of a religious faith, keep practicing it. It’s one of those prejudices you should not let go of easily. Find the campus ministry that fits your tradition; attend services, pray with others, learn and deepen your faith together. Whether you are religious or not, check whether the Love and Fidelity Network has a chapter on your campus, and consider starting one if it does not. The cultivation of virtue in all its dimensions, including the sexual, is not the counsel of fusty outmoded prejudices. It is the teaching of experience to the inexperienced.

One pitfall of the contemporary student that we didn’t have to worry about it in my day was the distractions of the internet, and especially of social media. It’s not just a problem for students: I might have finished this essay sooner if it weren’t for social media. For all of us these days, it takes discipline to stay focused on things that require more attention than tweets, gifs, texts, and the like. But we have books to read, research to conduct, papers to write, and thoughts to think that take longer to form than a half-baked tweet, and more effort than rapid thumb-texting. The self-mastery is worth it. You’ll have to find what works for you, whether it’s self-imposed quotas and curfews, periodic media-fasting, or saying goodbye to (some or all) social media altogether. Some of your professors may decree that their classrooms are tech-free zones: no laptops, tablets, or cellphones may be used. You should take this as what it is—a rule with your mutual good firmly in mind.

Speaking of those classes, I have said nothing about how you should go about choosing them, or choosing your major. Some other time, perhaps. For now, suffice it to say that there is nothing wrong in itself with being “practical” in obvious ways (engineering, accounting) or “impractical” in obvious ways (philosophy, literature). The only thing I will add on the subject here is that you should seek challenges. Not only challenges of an intellectual sort, that stretch your capacities and demand your best, but challenges to what you think and believe. You come to college with prejudices, remember. It is crazy to think they can or should all be thrown out with yesterday’s recycling. But learning means testing them to see which ones survive.

May the best prejudices win.