Every great thinker is subject to misrepresentation. Yet, perhaps because the political traditions of the twentieth century are so close to our own, every great twentieth-century thinker is subject to a particular kind of misrepresentation.

This misrepresentation is a circus act in which the thinker is assessed by a political tradition and transformed into a political partisan for or against the causes of the hour. The ringleaders of this circus act wish the thinker to perform for their audience, inciting appropriate emotions of praise or indignation toward that thinker. In this circus act, Leo Strauss, who hardly wrote about the United States and never wrote on foreign policy, turned into a neoconservative bear to frighten those opposed to the Bush administration and the Iraq War.

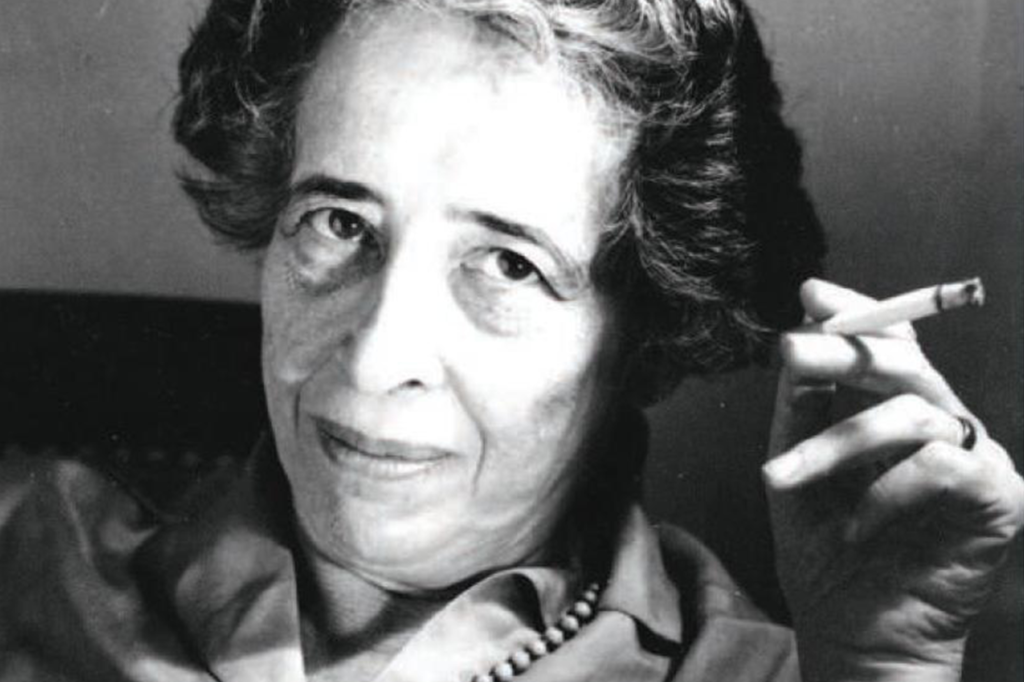

With Hannah Arendt, the circus act is rather different. Here, the circus ringleaders domesticate her to the political tradition of American liberalism, so that she can be brought out to cheer for liberal or progressive causes and galvanize resistance to the forces of reaction. Arendt, they assume, is on their side.

Following the political events of 2016, this circus act has become a regular feature in the flagship publications of liberalism. Within a month of the election, writers in The New York Review of Books invoked Arendt to oppose the impending inauguration. Keenly publicizing that Amazon had to restock Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism due to an increase of sales in early 2017, others use Arendt to draw readily applicable explanations for all of liberalism’s present bugbears, from the inability of left-liberalism to hold an effective political coalition, to the alt-right, to anti-Semitism, to sloganeering about the “banality of evil.” Activists all the way up to Chelsea Clinton do this. Turning Arendt’s profound phrase into a liberal cliché must dismay Arendt scholars; political theorist Corey Robin rebuked Clinton’s misuse of the phrase in a Twitter exchange, and the ensuing to-and-fro made it clear Clinton did not know what she was talking about.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.These circus acts are premised on a fake character. Letting Arendt speak for herself recovers her intellectual independence, as someone who defined herself apart from and against the political traditions of her day, including progressive liberalism. Indeed, letting Arendt speak for herself recovers her status not as someone who wished to align with any political movement, but as one who consciously sought the status of a pariah.

“I never was a liberal”

Serious commentary acknowledges that Arendt is not fully at home in the house of progressive liberalism. Yet its way of doing so is to note that while she espouses “many progressive causes,” her leftism is not quite enlightened enough. One recent essay, very typical of this genre, gleefully draws from Arendt to check all the boxes for the 2016 comparison—then admonishes her for not being quite as sensitive to class issues as she ought to have been, as well as for being too generous to eighteenth-century American constitutional democracy.

Yet measuring Arendt by the standards of American liberalism is the wrong way to understand her. She herself tells us. When asked about her politics, Arendt explicitly repudiated American liberalism. As she put it,

I don’t belong to any group . . . I never was a liberal . . . I never believed in liberalism. When I came to this country I wrote in my very halting English a Kafka article, and they had it “Englished” for the Partisan Review. And when I came to talk to them about the Englishing I read the article and there of all things the word “progress” appeared. I said: “What do you mean by this, I never used that word,” and so on. And then one of the editors went to the other in another room, and left me there, and I overheard him say, in a tone of despair, “She doesn’t even believe in progress.”

Arendt’s suspicions of twentieth-century American liberalism stem in large part from her repudiation of a concept central to the understanding of American liberalism: the concept of progress.

In On Violence, written after the 1968 student protests, Arendt extended her critique of “progress” to “progressivism.” She contended that American liberalism’s infatuation with the concept of progress drew from Hegel and Marx but sacrificed their intellectual rigor to construct a political movement that could rally disparate ideologies (liberals, socialists, and communists) and different demographics (student groups and the working classes) together. Arendt commented: “Inconsistency has always been the Achilles’ heel of liberal thought; it combined an unswerving loyalty to Progress with a no less strict refusal to glorify History in Marxian and Hegelian terms, which alone could justify and guarantee it.”

Arendt’s disavowal of progressivism for its intellectual contradictions extended to progressivism’s central political proposals. Since the early twentieth century, progressivism has attached the concept of progress to a particular political theory, seeing centralized government as the agent of progress because it purportedly renders government action more effective. Progressivism works to weaken federalism and bypass the legislative branch, concentrating power in the hands of the federal bureaucracy to create a new administrative state.

In the 1960s, enjoying supermajorities in Congress, American liberalism intensified this project. Arendt contended that this came at precisely the moment when European nation-states were discovering that centralized administration failed to achieve its promise:

And just when centralization . . . turned out to be counterproductive in its own terms, this country, founded, according to the federal principle, on the division of powers and powerful so long as this division was respected, threw itself headlong, to the unanimous applause of all “progressive” forces, into the new, for America, experiment of centralized administration—the federal government overpowering state powers and executive power eroding congressional powers. It is as though this most successful European colony wished to share the fate of the mother countries in their decline, repeating in great haste the very errors the framers of the constitution had set out to correct and to eliminate.

The Jew in the Modern World

More serious than the mischaracterization of Arendt’s political theory, however, is how the circus act mischaracterizes her activity of thinking: the way of life as a thinker that she wished to leave as an example for posterity. Informed by her self-understanding as a Jew, Arendt’s way of life was that of the pariah.

Arendt argued that the political circumstances surrounding the development of the nation-state give the Jews three basic choices for how to live. First, they give Jews the option and permission to assimilate. But for Arendt, to be Jewish is to be set apart. This is not a separation “made” by others, as Sartre thought, applying his existentialist postulate that no essence exists. It is not a separation “made” through a long history of Gentile mistreatment from the Middle Ages to the present, as the standard apologetic of Jewish history went. The assumption here is that once others stopped “making” Jews different, they could join humanity. What Arendt calls “permission to ape the gentile” is a false path.

Second, modernity gives the Jews the opportunity to play the parvenu. The parvenu assimilates, in the sense that he belongs to Gentile society and ascends to the heights of Gentile society. Yet he exaggerates a variety of social or psychological traits of “Jewishness.” He performs for his Gentile audience, playing a kind of affected, theatrical version of a Jew who is brought out to incite appropriate emotions in his audience. Arendt’s paramount example of the parvenu is Benjamin Disraeli, who played the role of the Jew to advance his political career and, winning the approval of his Gentile audience, to ascend the heights of English society.

Yet Arendt strongly condemns the parvenu. By allowing other political and social traditions to define him, the parvenu separates himself from the Jewish people and conforms to a society that discriminates against actual Jews. The parvenu helped turned Jews from a national or a religious group into a social or psychological character, “Jewishness.” The parvenu thus made twentieth-century antisemitism possible. Nineteenth-century antisemitism aimed either to convert Jews or to assimilate them. Since Jews seldom did either, they were generally left alone. But “Jewishness” cannot be assimilated or dissolved through conversion. It must be either accepted or eliminated.

In a way, those who domesticate Arendt to progressive liberalism turn her into a parvenu. They bring her out to perform for their agenda, raising her intellectual, political, and social stock to the extent it serves that agenda. When it no longer serves it—if, for instance, a wave of activists campaigned to purge Arendt from the curriculum because of her essay “Reflections on Little Rock,” her denunciations of the African-American student demands in 1968, and her misgivings about Brown v. Board of Education—she would be eliminated.

Arendt as Pariah

The counterpart to the Jew as parvenu is Arendt’s third option: the Jew as pariah. In an essay titled, “The Jew as Pariah: A Hidden Tradition,” Arendt writes that pariahs

did the most for the spiritual dignity of their people, who were great enough to transcend the bounds of nationality and to weave the strands of their Jewish genius into the general texture of European life . . . those bold spirits who tried to make of the emancipation of the Jews that which it really should have been—an admission of the Jews as Jews to the ranks of humanity.

On these terms, Arendt’s focus is on the celebration of the conscious Jewish pariah as a modern type. The pariah type extended to Arendt’s own self-understanding as a Jewish thinker. Just as in the Jewish case, a thinker must refuse to play the parvenu and refuse to be domesticated to the fashionable political currents of her own time. Just as in the Jewish case, the thinker is, for Arendt, a pariah.

She exercised this status as a pariah most notably in her report on Adolf Eichmann, for which she coined the phrase “the banality of evil” and for which she faced considerable social ostracism. Yet in the report, her determination was to reflect on the unprecedented crimes of the Holocaust in an unprecedented way—without relying on any political or philosophic tradition. The report was a free and frank exercise in thinking, not moderated or impeded for fear of social ostracism. In one of the debates with her critics, Arendt says:

What confuses you is that my arguments and my approach are different from what you are used to; in other words, the trouble is that I am independent. By this I mean, on the one hand, that I do not belong to any organization and always speak only for myself, and on the other hand, that I have great confidence in Lessing’s selbstdenken [thinking for oneself] for which, I think, no ideology, no public opinion, and no “convictions” can ever be a substitute.

Arendt recognized that thinking could turn the thinker into a pariah. But that is the role she adopted.

Reading Arendt in Our Culture

On Arendt’s terms, one of the most dangerous characteristics of our culture is its propensity to intellectual and social conformism on a vast scale. Mass conformism is, Arendt argued, a precondition for totalitarianism. In some ways it is reassuring to see American liberalism take an interest in totalitarianism. As François Furet observed, this has not always been so. During the 1970s and 1980s there was a dearth of such interest, in spite of the reality of the USSR. Yet those genuinely interested in totalitarianism and looking for guidance from Arendt should bear in mind that Arendt did not wish to teach others to subscribe to a political tradition. For Arendt, thinking needs “no pillars and props, no standards and traditions to move freely without crutches over unfamiliar terrain.” Thinking extends beyond the elite of the culture’s flagship publications: “every human being has a need to think.” Arendt’s exhortation for all human beings to think independently, even to the point of social ostracism or pariah status, remains the best counterpoison to mass conformism.