This essay is part of our series on the significance of the rise of the “Nones.” See the full collection here.

Growth in the number of Americans who profess no religious affiliation cannot but affect the institution of the family, built as it is on the marital union of husband and wife. The content we publish at Public Discourse centers around the five pillars of a thriving society, one of which is a healthy understanding of sexuality and family. As our description of this pillar states, “No other institution can top the family’s ability to transmit what is pivotal—character formation, values, virtues, and enduring love—to each new generation.” In this essay, I highlight how the absence of religion matters for sexuality and family, and how attitudes and practices in these respects are changing—quickly.

This is not a review piece. It’s not philosophical. I won’t speculate much on how we got here, nor will I talk about complex statistics or causal directions. I just want to introduce recent survey data—from November 2018—that provide a snapshot of what unreligious Americans think and do, with a few observations on how things have changed since 2015.

The Survey

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Let me offer a word about the survey. I call it the American Political and Social Behavior survey, which interviewed 5,285 Americans in November 2018, just days after the midterm election. The data collection was conducted by Ipsos, formerly Knowledge Networks (or KN), a research firm with a very strong record of generating high-quality data for academic projects. They maintain the KnowledgePanel®, a well-regarded survey pool which does not accept self-selected volunteers. As a result, it is a random, nationally representative sample of the American population, and it compares favorably with other large population-based data collection efforts. I asked a series of identical questions in early 2015 in an even larger sample from the same firm—hence the ability to discern trends.

What do I mean by “unreligious” here? For this essay, it’s all adults between the ages of twenty and sixty who said, when asked about their present religion, that they were “nothing,” atheist, or agnostic. They amounted to 20.3 percent of this sample. That number does not include respondents who said they don’t know what they are, as well as the 10.4 percent who identified as “spiritual but not religious,” a group whom the unreligious resemble in lots of ways. We asked all respondents how often they attend religious services—not counting events like weddings and funerals—and 96 percent of the unreligious group said they either never attended, or did so once or twice a year.

I compare these two groups with Catholics and evangelical Protestants. The second of these was constructed by taking the sub-sample of respondents who said they were either Protestant or “other Christian,” to whom I posed a follow-up question about a theological self-identity. These are the evangelicals, which constitute just under 10 percent of the sample. Catholics make up 24 percent. Keep in mind that “religiosity” is not included in these measures. This is an overview of religious self-identity—not about how active people are in their faith.

Marriage and Cohabitation Practices

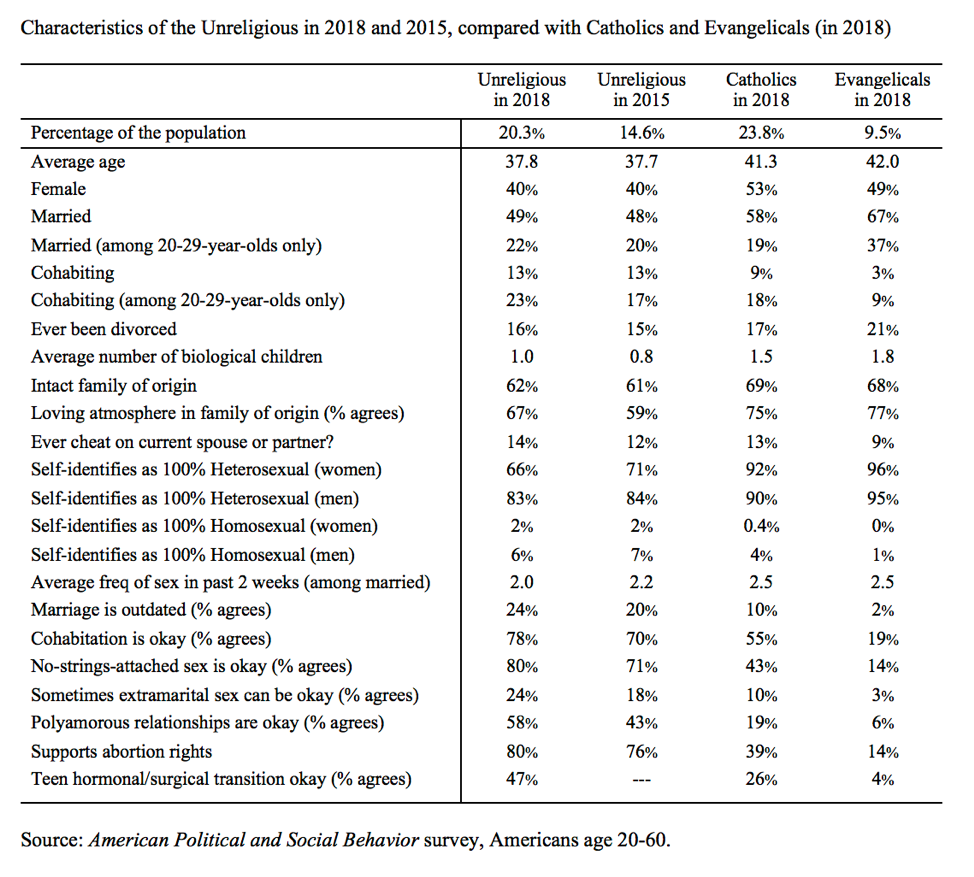

What do we learn? What is the unreligious population in America like, and how are they changing? The table below tells us. What you see is basic frequencies and averages, without controls for age, sex, etc.

The unreligious are, on average, slightly younger than Catholics and evangelicals, and notably more male (60 percent). This is old news. The unreligious are pretty conventional when it comes to their marital status, but, as we’ll see below, they are much less so when it comes to their attitudes about marriage. Forty-nine (49) percent of them are currently married. That’s not so far removed from Catholics (58 percent) but well under evangelicals (at 67 percent). Even when I limit the group to respondents below age thirty—which is just north of the median age at marriage in the United States—it is notable that 22 percent of the unreligious are married and 23 percent are currently cohabiting, not radically different from the 19 and 18 percent of Catholics that are married and cohabiting, respectively. For comparison, 37 and 9 percent of younger evangelicals are married and cohabiting, respectively. The cohabiting habits of the unreligious, however, have shifted—note the uptick in cohabitation—six percentage points in just under four years. That amounts to a 35 percent increase. Since it’s unlikely that the unreligious have recently changed their minds about the morality or pragmatics of living together, my bet is in the other direction: cohabiting leads many to no longer identify as religious at all.

The unreligious, curiously, are unlikely to have ever been divorced—at 16 percent, they’re virtually tied with Catholics. They are, however, several years younger than Catholics, on average, and have been exposed to less risk of divorce (by being younger and less apt to marry).

Unreligious Americans are not a very fertile bunch. Of course, that’s not saying a whole lot, given that the American fertility rate—the number of births a woman is expected to have in her childbearing years—continues to drop. It’s now down to 1.73, a historic low. But the unreligious are even less likely to have children; they report, on average, one biological child, notably less than Catholics and evangelicals but slightly more than in 2015.

Their own parents were slightly more apt to have split; 62 percent of them (in 2018) said their parents are still married, or were married until one or both of them passed away. The same pattern is the case with their reports of a “loving atmosphere” in their family of origin. That number is a bit lower than that of Catholics and evangelicals, though not profoundly so.

Overall, the family behavior of the unreligious is not all that radical. Yes, they are perhaps slower to get married, and a bit less likely to do so, but the patterns are not nearly so dramatic as one might expect, given all the chatter about a surging population of godless Americans. Even their “cheating” behavior is not all that remarkable, nearly in step with Catholics and not twice as high as evangelicals. The only notable change since 2015 is in more cohabitation.

Attitudes about Sexuality and Marriage

On matters of sexuality, however, there are more obvious differences and significant change. Sexual orientation is not widely believed to be binary, but for the sake of brevity I’m only reporting here on heterosexual and homosexual self-identities. I split the sample by sex, since men and women tend to diverge some.

Only 66 percent of unreligious women say they are “100% heterosexual (or straight),” a figure dramatically below the 96 and 92 percent of American women who identify as evangelical Protestant and Catholic. And it’s dropped five points in four years. Comparable patterns (but no changes) are evident among men, where heterosexuality is more common: 83 percent of unreligious men are straight, while 6 percent of them report being gay. Among the 200 evangelical women who completed the survey, not a single one reported a homosexual orientation. The same is the case for Catholics: only two of 401 female Catholics identified as homosexual. As is the case in the United States, so in this sample: male homosexuality is notably more common than female homosexuality.

Despite the permissive reputation of the unreligious, their actual marital sexual frequency is lower than that of Catholic and evangelical couples—at two instances in the past two weeks. As has been documented extensively in the past few years, the frequency of sex among American couples—whether cohabiting or married—has been declining at statistically significant rates. This pattern has not spared the godless.

When we consider attitudes about marriage and sex, the gap between the unreligious and Catholics and evangelicals begins to widen considerably. In fact, on each of seven attitude measures I examined, the unreligious are notably more permissive than even the spiritual-but-not-religious (not shown). Nearly 80 percent of unreligious Americans agree (or strongly agree) that cohabitation is okay, no-strings-attached sex is okay, and abortion should be a legal right. This is all unsurprising. But even some of the more radically “progressive” attitudes demonstrate strong support among the unreligious: 24 percent agree that it is “sometimes permissible for a married person to have sex with someone other than his/her spouse.” (I thought perhaps women would differ from men here, but they didn’t—or at least not by much.) Although few Americans are actually in polyamorous living arrangements, the unreligious would support them should someone choose such an arrangement; 58 percent of them agreed that “it is okay for three or more consenting adults to live together in a sexual/romantic relationship,” a percentage that is far more supportive than Catholics or evangelicals. Among the latter, only 6 percent thinks polyamory could be okay.

A more interesting theme, however, is the surge in support for such alternatives. On each statement, note the rise in agreement that has occurred in just under four years. Polyamory tops the list—a 35-percent leap in the share of unreligious who now endorse polyamorous arrangements (from 43 to 58 percent). Even support for extramarital affairs grew by one-third (from 18 to 24 percent). The unreligious aren’t alone here. Catholics, too, have witnessed liberalization in attitudes. Evangelical numbers display a more modest uptick, and from lower starting points.

Finally, the matter of transgender youth has received a great deal of attention of late. I posed a question I believed to be at the fringe of permissive when I asked respondents if they thought it was okay “for adolescents to transition with hormones or surgery if they identify with another gender.” For context, surgical transitions for teens who think they’re in the wrong body remains a move that few pediatricians have the stomach to recommend and even fewer “gender clinics” agree to perform. Hormonal transitions are far more apt to be the limit, until patients are no longer minors. But that doesn’t stop unreligious Americans from endorsing methods including surgery. Just under half of them agree that this is okay. Women tend to be more supportive than men: 40 percent of unreligious men agree with such transitioning, well below the 58 percent of women who do so. By contrast, only 4 percent of evangelical women were willing to support this approach, well below the 28 percent of Catholic women who did. I didn’t ask about transgender transitions for teenagers in 2015. (Not many surveys did.)

The Future of Unreligious Americans and Social Change

Unreligious Americans are growing in number, so whatever you see here you will likely see more of in the near future. In fact, the unreligious answer (“nothing,” agnostic, or atheist) to the question about religious affiliation grew by 39 percent since I last fielded an identical survey item in the first month of 2015. That’s an impressive rate. Their growth is not natural, as the fertility indicator reveals. It’s social. But that doesn’t make it any less remarkable. In fact, it’s a signal that a great deal of “inverse” proselytization is going on. Americans are losing their religion, whether passively or actively.

Where is the ceiling? Several years ago, a set of demographers projected a top end estimate of 17 percent (in the General Social Survey, whose religious question is asked slightly differently than mine) in the year 2043. That study curiously projected neither growth nor decline in the unreligious over time. Who’s right? Only time will tell.

But one conclusion seems obvious: permissive sexual attitudes and practices have not stimulated the religious revival many Christians claim the Sexual Revolution will yet yield. I see no evidence of it. On the contrary: Christians seem to grow more complicit—or at least more quiet about their misgivings—by the year.