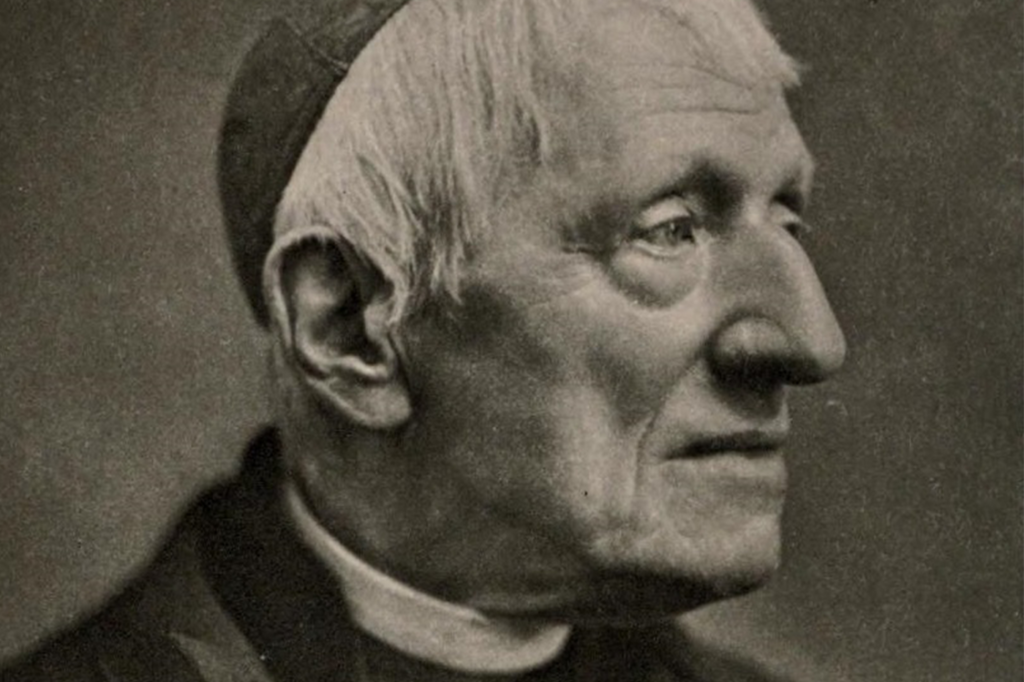

In February of this year, news came from Rome that Pope Francis had cleared the way for the canonization of John Henry Newman (1801–1890), the celebrated nineteenth-century theologian and Oratorian priest, who midway through his life converted from Anglicanism to Roman Catholicism. When the canonization takes place, it is likely to reignite discussions about the significance of Newman’s legacy.

Newman has been many things to many people. He clearly possessed a conservative outlook on divine revelation and humanity’s standing before God. But he also advanced ideas—such as doctrinal development and the responsibility of the hierarchy to consult the faithful—that went beyond the standard ways in which Catholic theologians had thought. In light of these tensions, how are we best to understand the work of this holy priest and scholar, who exercised such a profound influence on modern Catholic theology?

Relatively late in life, Newman offered his view on the unifying purpose behind his various projects in the memorable “Biglietto Speech” (which he delivered in 1879 upon receiving word that he had been named a cardinal). In that speech, Newman confessed his own inadequacies, noting that over the course of years he had “made many mistakes” and that his work lacked “that high perfection which belongs to the writings of Saints.” Despite these shortcomings, there was, Newman asserted, an underlying continuity to his efforts, one in which he took pride:

I rejoice to say, to one great mischief I have from the first opposed myself. For thirty, forty, fifty years I have resisted to the best of my powers the spirit of liberalism in religion. Never did Holy Church need champions against it more sorely than now, when, alas! it is an error overspreading, as a snare, the whole earth.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.

In response to the temptations of liberal religion, Newman articulated a profound vision of conscience as a natural mode of hearing God’s voice. He brought this concept into relation with ecclesiastical authority, which he saw as a divinely ordained assistance for rooting out errors in moral judgment. Newman’s insights on these matters, though addressed to specific challenges that Catholics faced during his lifetime, remain important resources for resisting the spirit of liberalism in religion today.

Newman’s Thoughts on Conscience

Some have speculated that, when Newman is canonized, the Holy Father will also bestow on him the title Doctor of the Church (Doctor Ecclesiae) and specifically “doctor of conscience.” If Newman receives this honor, I hope that those who are interested in the question of conscience will attend closely to what he actually wrote, rather than speculate based on a few snippets of his writings.

We hear a lot of talk these days about the “primacy of conscience,” and, with the proper qualifications, Newman’s writings could support this idea. But that concept can also be employed in ways that contradict what Newman said about conscience, and it’s important that we not put Newman’s authority behind ideas that he never would have defended.

Newman touched on conscience at various places in his writings, but his most notable discussion of it can be found in his essay on papal authority, titled A Letter to the Duke of Norfolk (1875). There Newman memorably described conscience as “the aboriginal vicar of Christ.” By this phrase he intended to highlight that it is in and through our conscience that we first hear the voice of God. As Reinhard Hütter rightly observes, Newman’s understanding of conscience is “essentially theonomic,” that is, it has divine law as its foundation: “Conscience is not simply a human faculty, but is in its root constituted by the eternal law, the Divine Wisdom communicated to the human intellect. It is upon its theonomic nature and upon it alone that the prerogatives and the supreme authority of conscience are founded.”

This theonomic framework totally dispels any notion that Newman’s emphasis on the primacy of conscience could lead to subjectivist or relativist ethics. Newman took precautions against this potential misconception by distinguishing between conscience, rightly understood, and a counterfeit understanding of conscience, which had wormed its way into the popular mindset. As he put it:

Conscience has rights because it has duties; but in this age, with a large portion of the public, it is the very right and freedom of conscience to dispense with conscience, to ignore a Lawgiver and Judge, to be independent of unseen obligations. . . . Conscience is a stern monitor, but in this century it has been superseded by a counterfeit, which the eighteen centuries prior to it never heard of, and could not have mistaken for it, if they had. It is the right of self-will.

This notion of conscience as “the right of self-will” has become ever more pervasive since Newman’s time. Newman’s stance on conscience, then, was not only countercultural but also prophetic. If persons of faith today are to avoid being tossed here and there by “false liberty of thought” (as Newman called it in his Apologia pro Vita Sua), we will have to hold fast to the theonomic understanding of conscience that Newman articulated.

Conscience in Relation to Church Authority

Because Newman understood conscience as theonomic, he consistently emphasized that the central concern of the moral life is to discern what God requires of us. In matters of moral inquiry, God has not left us stumbling in the dark, but has given us the Church, which can speak authoritatively on questions pertaining to divine and natural law.

From Newman’s vantage point, then, ecclesiastical authority is a gift, not a burden. The Church can bind our consciences because her leaders speak with the authority given by Christ to the Apostles. That the modern world ignores the voice of the magisterium is not a mark against the Church’s authority; rather, it is testimony to humanity’s persisting rebellion against the will of God.

This facet of Newman’s theology runs counter to the liberal notion that the individual is master over his own life. As Newman puts it in the Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, the divine law is “the rule of ethical truth, the standard of right and wrong, a sovereign, irreversible, absolute authority in the presence of men and Angels.” A conscience that is attuned to the divine law is “a stern monitor.”

Too often, however, we become indifferent to the voice of conscience. Because of sin’s effects on the mind, our “sense of right and wrong [is] easily puzzled, obscured, [and] perverted.” Consequently, God has given us the Church to guide us along the right path: “The Church, the Pope, the Hierarchy are, in the Divine purpose, the supply of an urgent demand. Natural Religion, certain as are its grounds and its doctrines as addressed to thoughtful, serious minds, needs, in order that it may speak to mankind with effect and subdue the world, to be sustained and completed by Revelation.”

Nevertheless, Newman did not counsel unthinking obedience on the part of the Church’s members. For Newman, conscience and ecclesiastical authority exist in a dynamic interrelationship. The Church does not rule by fiat, but appeals to the consciences of the faithful, who are ultimately answerable to God.

This is the import of Newman’s famous quip about raising a glass to conscience first, and then to the Pope. Were a pope (or any other holder of church office) to denigrate conscience, he would in effect saw off the very branch on which he sat. For whenever ecclesiastical authorities uphold some facet of the moral law, they make a direct appeal to the consciences of persons of good will.

The Infidelity of the Future

Because society in general was drifting away from a traditional understanding of conscience and its relation to divinely established authority, Newman anticipated a coming age of infidelity. Arguably his most dire prophecy was this: “The trials which lie before us are such as would appall and make dizzy even such courageous hearts as St. Athanasius, St. Gregory I, or St. Gregory VII. And they would confess that dark as the prospect of their own day was to them severally, ours has a darkness different in kind from any that has been before it.” In this area of his thought as well, Newman’s anti-liberal instincts were manifest. Newman was no naïve optimist, and he remained skeptical about narratives of uninterrupted progress.

In spite of his criticisms, Newman recognized certain positive aspects of the liberal tradition. In the Biglietto Speech he readily admitted “that there is much in the liberalistic theory which is good and true; for example, not to say more, the precepts of justice, truthfulness, sobriety, self-command, benevolence, which . . . are among its avowed principles, and the natural laws of society.”

It is precisely on account of these characteristics, however, that liberalism can play such an insidious role in society. As Newman warns in the same speech, “There never was a device of the Enemy [Satan] so cleverly framed and with such promise of success.” If we are not careful, we are liable to mistake the attainments of liberal society for the inbreaking of the kingdom of God, and lose sight of the ultimate destiny to which humans are called.

The battle in which Newman fought has not ended since his death. If anything, it has intensified. Newman’s contention that “[n]ever did Holy Church need champions against [liberalism] more sorely than now,” just as readily applies to our own context.

Of course, we should be careful not to conflate the “liberalism” that Newman opposed with the word as it is commonly used today. Certainly, there are errors intrinsic to contemporary political liberalism that need critiquing, but that conversation is distinct from the struggle against the spirit of liberalism in religion, which demands unqualified resistance. In the Biglietto Speech, Newman specifically described this strand of liberalism as “the doctrine that there is no positive truth in religion, but that one creed is as good as another.” This outlook teaches that “[r]evealed religion is not a truth, but a sentiment and a taste; not an objective fact, not miraculous; and [that] it is the right of each individual to make it say just what strikes his fancy.”

As his words indicate, the preeminent object of Newman’s concern was religious indifferentism. With great prescience, he recognized how a relativistic approach to religious differences corrodes the foundational claims of the Christian faith. If, as the Church confesses, the Incarnation is the central fact of history, then the person of Jesus demands our undivided allegiance. The confession of Christ as Lord simply cannot be squared with the notion of religion as a mere sentiment.

During Jesus’ public ministry, he posed the question to his disciples, “Who do you say that I am?” How we answer that question—in the time and in the place that God has ordained for us—will have all sorts of ramifications for the lives of our families and of our communities. So even though one may distinguish between the spirit of liberalism in religion and present-day political liberalism, the topics are not unrelated. One of the myths of the liberal tradition, as inherited from such thinkers as John Locke and J.S. Mill, is that there exists a strict demarcation between religious practice, which liberalism treats as a private matter, and our political existence, which is lived out in the public square. But if religion fundamentally has to do with that which ties or binds a community together (as in the classical sense of religio), then it can never be a matter of merely private concern.

By refusing to separate the natural and supernatural ends of human existence, John Henry Newman’s antiliberal stance pointed us toward a truly integral form of life—one that has the potential to renew a dying culture.