Stolen valor is a serious, public wrong. Those who have earned insignia, medals, and ribbons in sworn service to our nation deserve all the honor that we can bestow on them. And those who impersonate such heroes deserve all the disapprobation we can muster. To pose falsely as a decorated veteran (“to steal valor”) is to expropriate some part of the honor due to another. And it trivializes true military service, the willingness to die in defense of one’s fellow citizens.

So, stolen valor is a serious offense. But when perpetrated incompetently, its results can also be amusing. The Internet is full of images of men whose chests sag under the weight of more medals than one could possibly earn in even the most distinguished military career. Some impersonators combine elements of uniforms from different services or ranks. And while the services have very specific requirements for the placement of items on uniforms (down to the fraction of an inch), valor thieves often pin stuff all over the place in manifest disarray.

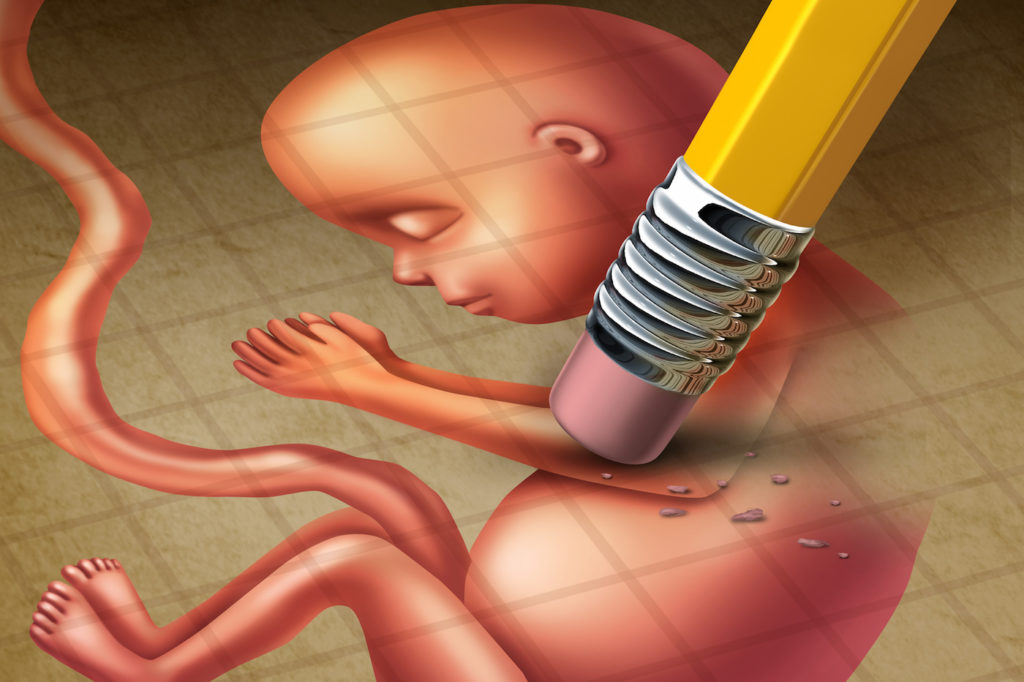

Those images come to mind when reading the per curiam opinion in Hodes & Nauser MDs v. Schmidt, a case in which the Supreme Court of Kansas discovered a “natural right” to perform abortion by dismemberment. In a case of stolen jurisprudence, a majority of the justices impersonated learned jurists and competent legal philosophers. The result was simultaneously grievous and amusing.

Elizabeth Kirk has already discussed the grievous aspects of the ruling here at Public Discourse. The court struck down a state statute that prohibits abortion by dilation and evacuation (“D&E”). In a D&E, as Kirk explained, “the unborn child is dismembered while still alive. He or she is then extracted from the womb one piece at a time.” A majority of justices ruled that the prohibition offends Section 1 of the Kansas Constitution which, echoing the United States Declaration of Independence, declares that all “are possessed of equal and inalienable natural rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” This holding is manifestly implausible, as Kirk demonstrated, and the ruling radically threatens the protections that the rule of law affords to citizens—the powerful and vulnerable alike.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.This essay considers the humorous incompetence of the opinion, not for amusement but to learn an important lesson. American constitutions contain terms of art taken from common law, including terms that refer to peculiarly Anglo-American doctrines of natural rights. If we want judges to understand and apply those terms correctly, then we must recover that tradition. Otherwise, judges will make things up, as they did in Kansas.

Poor Philosophy Posing as Legal Reasoning

Like a man wearing an Army beret with a Marine Corps coat and a Legion of Merit medal on the wrong side, the Kansas justices festooned their per curiam opinion randomly with impressive terms. They slapped on “natural rights,” “inalienable rights,” “absolute rights,” “autonomy,” “Locke,” “Coke,” and “Blackstone.” Their license to use the terms was manifestly not earned by the slightest effort to learn the terms’ meanings. In fact, sometimes the justices used the terms interchangeably, much as a valor thief might carelessly refer to his “silver star” while pointing to his Meritorious Service Medal.

For example, the court asserts that among the natural rights protected by Section 1 is “the right of personal autonomy, which includes the ability to control one’s own body, to assert bodily integrity, and to exercise self-determination.” Autonomy and bodily integrity free “a woman to make her own decisions regarding her body,” including the decision whether to have an abortion. To the extent that this means anything, it is plainly false.

Section 1 does not mention autonomy, because autonomy is not a legal concept. It comes from philosophy, and is recent in origin—and the justices proved that they have not read that philosophy. Bodily integrity is a product of a legal doctrine, the law of battery, from which is derived the doctrine of informed consent. The justices apparently did not consider that concept, either.

A D&E is not done by one person. It requires both a mother and an abortionist. (It also concerns a third person, whose autonomy the justices ignored, but leave that aside for the moment). As the best-known philosophical defenses of the idea make clear, personal autonomy requires both a variety of morally valuable options from which to choose and freedom from coercion by others. Similarly, the doctrine of informed consent concerns the right to refuse medical treatment. The right it secures is a right not to suffer a battery or other interference with one’s body.

So, autonomy and bodily integrity protect a right not to administer or suffer a D&E procedure, but they cannot justify a right to perform or obtain one. To see this, consider that a patient has no right to require a doctor to remove a kidney from her body. A good doctor would lawfully and reasonably refuse as long as the kidney is not cancerous and is not otherwise posing a serious threat to the rest of the body. Conversely, a physician has no legal right to remove even a diseased kidney without the patient’s informed consent. To remove a kidney or an unborn human being from a human body without informed consent is battery, an ancient legal wrong. Both the patient and the physician have moral and legal rights not to participate in the procedure, so neither’s autonomy can justify requiring the other to participate.

Abortion advocates might mean that the mother–abortionist duo is autonomous with respect to the state―but this is obviously false. A doctor who routinely removes healthy kidneys from patients is a bad doctor. He is a threat to public health. The political community has the right to interfere in his medical practice and the state is justified in punishing him. He has no autonomous right to practice medicine badly.

Furthermore, unborn human beings are not kidneys, and a D&E is not just like a nephrectomy. The court did not explain how an abortionist’s obtaining the woman’s informed consent justifies the long-term effects of a D&E on the mother, nor how it respects the natural right of the human being inside her not to be torn apart limb from limb and removed from the mother’s body. Had the justices bothered to check, they would have learned that the rights of life and limb are absolute, natural rights in our common law, unlike the right to perform a D&E.

Judicial Activism Posing as Common Law

The legal reasoning in the opinion is as unmeritorious as the philosophy, both in its particular decorations and in its general appearance. The court purported to interpret the phrase “natural rights” in light of the common law, our Anglo-American tradition of customary law within which our legal concepts of natural rights grew. As I have argued at Public Discourse before, that is indeed how one should interpret constitutional terms that are taken from the common law. When a constitutional text employs common-law terms of art, it incorporates by reference the doctrinal contours and implications of the legal concepts to which the terms refer. But the court’s exercise revealed that all but one of the justices do not know what the common law is.

Throughout its discussion, the court identifies “common law” with judicial opinions. It thus shoehorns innovative judicial decisions into its discussion of “natural rights.” Unfortunately, it is now a commonplace error to identify common law with judge-made law, but that conflation is particularly ludicrous in the Hodes & Nauser opinion. The justices insist that common-law rights are simultaneously natural and pre-political (emanating from reason and custom before the creation of states and courts) and judge-made (emanating from innovative judicial opinions). And they make no attempt to address this incoherence.

The opinion’s use of particular terms is equally inept. In explaining why the rights secured by Section 1 are judicially enforceable, the court made heavy use of the term “inalienable.” The court took the term to mean that the rights are “meaningful” and not mere “rhetorical flourishes.” “So,” the court concluded, “when the State attempts to use its police power to unconstitutionally encroach on these inalienable rights, we have an obligation to ensure it does not.” (The emphasis is in the original.)

But “inalienable” does not mean that rights are meaningful and judicially enforceable. As any student in a first-year property course knows, it means that the rights can’t be alienated. A right or resource is alienable if it can lawfully be sold or given, and it is inalienable if it cannot. An automobile is alienable; a professional license is not. An easement appurtenant to land is alienable; a personal easement generally is not.

Phillip Muñoz has shown that the term has more or less the same meaning when applied to fundamental rights secured by the documents of the American Founding. An inalienable natural right is one that cannot be alienated in a social compact. For example, religious liberties such as the right of conscience are inalienable because they cannot be exchanged for an analogous civil right in a constitution or other social compact. Alienable natural rights, such as natural property, can be given up by consent in exchange for the more secure civil property rights that political society offers. Inalienable rights cannot.

What could it mean to have an inalienable, natural right to a D&E procedure? Such a right could not exist in a state of nature before the invention of a medical profession, scalpels, forceps, anesthesia, and waste disposal services. Far from being natural and inalienable, the right is entirely contingent upon social conditions that are developed by markets and the medical profession, and are all formed within a society’s legal norms and institutions.

The opinion also conflates terms of art that have different meanings. For example, it confuses inalienable rights with rights of property and estates, which are alienable in most respects. It runs together the common-law right of personal liberty with other “absolute rights,” without any apparent appreciation of what that term means. In common law jurisprudence, to say that a right is absolute is not to say that the law cannot place limits on it. To the contrary, absolute rights are inherently limited by the law of wrongs. That a right is absolute means merely that the state cannot take it away without first showing, in a proceeding that affords due process, that the right-bearer already relinquished the right in an act of wrongdoing.

As shown above, the court hung the informed-consent bauble on its lapel upside down. The claimants in the case are abortionists who seek the liberty to perform abortions. To invent such a right and excuse the physicians from the law, the court invoked a legal doctrine that prohibits physicians from performing medical procedures except on terms established by law.

A valor thief sometimes can deceive not only the willingly gullible but also innocent people with no military experience. Similarly, the per curiam opinion in Hodes & Nauser trades on ignorance of the common law―and it adds to the confusion about what genuine common law and natural rights are.

The Need for Real Jurists

The judges who authored and signed the opinion hold judicial office―but they are obviously not jurists. They stole the valor of the jurists whose names they pinned on their opinion. To anyone who has studied the common law and legal philosophy, it is obvious that the Hodes & Nauser decision was stitched together in the scrap bin of a jurisprudence surplus store.

Unfortunately, few lawyers and philosophers today read great jurists. As a result, few are able to spot impostors. Like uniform regulations, the specifications of natural law and natural rights that are found in American law and constitutions are not axiomatic and obvious to all. They must be learned.

There is a simple remedy for stolen valor: show the impostor to be preposterous. Though the offense is serious, exposing the humor of the act deprives the impostor of the honor he tried to steal and separates him from those who secure our lives and liberties in acts of honorable service. But of course, the joke is funny only to those who know what the uniform is supposed to look like.