The Christian understanding of the created order is fraught with danger. Christians must carefully avoid two opposing forms of error. On one extreme, there is the tendency to conflate the created with the Creator, which leads to a kind of paganized divinization of the world. On the other, there is the temptation to conclude that this world holds merely illusory value and therefore can essentially be ignored or abused. A proper approach to the created order, however, holds together the temporal and the eternal, properly relating and valuing them both.

This is a challenge for all Christian traditions, but has been especially acute for Protestantism. The Reformed tradition, in particular, has often been accused of having (and, in some cases, has understood itself as having) a pervasively negative view of the fallen world, leading to a devaluation of God’s creation. A major theme of the Reformation and its inheritors, however, is the need to rightly discern the ways that God continues to work, in preservation as well as redemption, amidst the realities of sin.

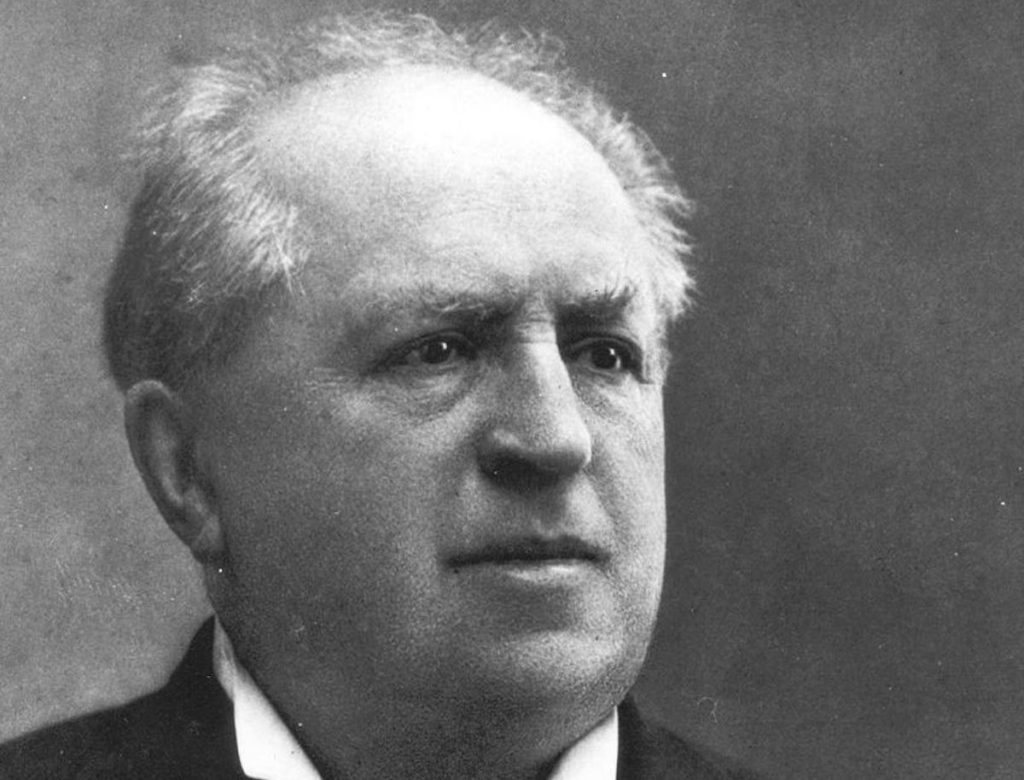

The Dutch Reformed theologian Abraham Kuyper (1836-1920) engaged these challenges directly through his articulation of the doctrine of “common grace.” This doctrine is one of the most significant—and controversial—aspects of the great theologian’s legacy. A new multi-volume translation of his exhaustive treatment of the doctrine is intended to provide deeper insights into Kuyper’s understanding of this crucial, and oft-misunderstood, element of divine action. Kuyper’s work sheds light on the moral significance of common grace, especially for natural law, social order, and our contemporary challenges.

Common Grace and Natural Law

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.For Kuyper, common grace was clearly grounded in Scripture and was taught but not fully developed in the historic Reformed faith. In doctrinal terms, Kuyper saw common grace as necessary for a full understanding of special, saving grace and of the underlying continuity of God’s faithfulness to his creation. Common grace also helps us to understand how there can so often be such genius and goodness in the world of unbelievers.

Common grace is a multifaceted concept for Kuyper. Indeed, it reflects the diversity and scope of all of God’s creation. A critical aspect of that creation is its moral order. God has created human beings in his image, and this means that human beings are moral agents. This moral agency entails instructions and responsibilities. Humans have been placed as stewards over creation, and their responsibility includes adherence to the moral order that God has instituted. A classic way of articulating this dynamic in Christianity is the rich and diverse tradition of natural law. God has created human beings in a certain way, with a particular set of powers, talents, skills, and habits, aimed at corresponding goods and ends. There is a law that governs the natures that God has created, a law that is fitted to and appropriate for all these different creatures, from sticks and stones to human beings and angels.

The fissure that sin creates affects every aspect of existence, but it does not erase the moral demands that are placed upon humans by their nature and by God. That anything continues to exist of humanity after the fall is an act of grace, and that the moral obligations that govern human nature are not completely lost or eradicated is likewise evidence of God’s ongoing gracious activity. Kuyper writes that “thanks to common grace, the spiritual light has not totally departed from the soul’s eye of the sinner. And also, notwithstanding the curse that spread throughout creation, a speaking of God has survived within that creation, thanks to common grace.” Here Kuyper stands in line with Calvin, who, notwithstanding a strong accent on human depravity, can nevertheless insist that recognition of moral reality is “implanted in the breasts of all.”

We may therefore understand the existence and acknowledgement of natural law after the fall as an aspect of God’s broader sustaining and preserving grace. This is a significant, and often controversial, teaching. And although Kuyper and the later neocalvinist tradition has often been described, and understood by its own devotees, as in opposition to natural law, Kuyper himself is quite clear: natural law is a manifestation of God’s common grace.

Common Grace and Social Order

One of Kuyper’s great insights is that God’s preserving work of common grace helps us understand both civic righteousness and the ongoing realities of social life.

The final volume of his trilogy on common grace focuses specifically on working out the implications of these moral and theological realities for social life. For Kuyper, the church could in some sense be said to be present wherever there are children of God, whether in the state of integrity or after corruption. But the church as an institution specifically formed around special grace is a feature of the post-fall situation. Similarly, there may be a sense in which political life could be said to exist in the primal condition, but it is only after the fall in sin that government takes on its distinctive character as a coercive power for the administration of civil justice. The state is, in this sense, the institution of common grace par excellence. It provides a curb on social evil, and a check on sinful ambition.

For Kuyper, the state is a necessary institution for the preservation of social life in the fallen world. But as his distinction between sphere sovereignty and state sovereignty indicates, even if the government is a particularly salient example of a common-grace institution, it is sharply limited by the legitimate and warranted functions and roles of other institutions. Two examples of special notice are the family and work, realities that are embedded in the nature of creation and reaffirmed in the curse and promise.

In a remarkable treatment of Adam and Eve’s fall into sin and the divine discourse in Genesis 3, Kuyper underscores the fundamental functions of procreation in marriage and co-creation in work. When God demurs from striking down Adam and Eve immediately, he preserves them in life in the face of death. As Kuyper observes, “Over against death stands life; and for life two things are necessary, namely, the emergence of life and the maintenance of life.” Family and procreation represent the basis for the emergence of human life, while work and co-creation represent the basis for the maintenance of life.

Kuyper highlights the foundation of grace that provides for the ongoing existence of and care for human life. To the woman God says, “in pain you shall bring forth children” (Ge 3:16). The element of the curse is present with the imposition of painfulness; but the element of grace is present in the promise: “You shall bring forth children.” Despite their sinfulness and the threat of death that they deserve, Adam and Eve will have children, and humanity will continue to exist. The woman becomes Eve, mother of all the living, a promise of life in the face of sin, death, and damnation. Kuyper writes,

Had absolute death set in, then the mother in Eve, from which our entire human race had to come, would be closed forever. And behold, the opposite happens: the womb of all human life is opened up. The Lord says, ‘You shall bring forth children.’ This, if you will, is the word of creation to which we and everyone called human owe our being. Here, therefore, life instead of death is at work.

The same is true for Adam and the productive labor that is necessary for the maintenance of human society. God says to Adam, “By the sweat of your face you shall eat bread” (Ge 3:19). The element of the curse is present in that work now has become toilsome and troublesome, painful and difficult. But the element of grace shines through in the promise: “You shall eat bread.” So just as God works through procreation to guarantee that human beings will continue to exist, God promises that through work human beings will get their daily bread.

Through spheres like the state, family, and work God’s common grace preserves, protects, and promotes social life. Thus, a proper understanding of God’s work in the world leads us to thankfulness and guides us in faithfulness.

Common Grace and Contemporary Crises

One of the benefits of a Kuyperian vision of God’s sustaining activity in the world is that it provides us with a reliable basis for engaging the social crises of our times. A consequence of the reality of common grace is found in Kuyper’s understanding of “sphere sovereignty,” which addresses the diversity, vitality, and dynamism of the social order. From the fallout of revolutions, whether political, economic, sexual, or otherwise, a recognition and appreciation for common grace and the moral order allows us to discern what is good, true, and beautiful amid the chaos of a fallen world. Both realities must be given their due: the continued goodness of the created order and the ongoing corruption wrought by sin, death, and the devil.

In his own time Kuyper applied his insights in a wide variety of areas, including politics, church life, economics, education, and the family. He was a statesman, a theologian, a journalist, and a social reformer. In 1891, for example, he comprehensively and prophetically addressed the “social question” in a way that complements the insights promulgated earlier that year of Pope Leo XIII in Rerum novarum. For Kuyper, common grace addressed a lacuna in the legacy of the Reformation teaching about divine grace and provided a firm foundation for acting as subjects of Christ the king in this life. It was out of this conviction that his own remarkable attempts at faithfulness derived.

An overemphasis on special grace could lead to the devaluation of the world and a retreat from the call to responsible stewardship in this life. And a fetishizing of common grace also has its dangers, including worldliness and accommodation of sin. But a proper understanding of created nature and divine grace makes truly faithful discipleship possible, and Kuyper’s rich explorations of common grace are a critical aid on that journey.