The first time I ever heard the expression “sex-change operation” was in the 1970s, when I learned that the noted travel writer James Morris had had such an operation and henceforth was to be known as Jan Morris. Morris later wrote a memoir that opens with the sentence, “I was three or perhaps four years old when I realized that I had been born into the wrong body, and should really be a girl.” He was in his mid-forties when he underwent surgery to become the woman he was already certain he was.

But has Jan Morris (now over ninety) ever actually been a woman? And was it even possible for James Morris to have been “born into the wrong body”? Today, when the number of Jan Morrises has proliferated and an ideological transgender movement has begun to force changes in law and policy, more and more people are saying “yes, of course” in answer to both these questions. In truth, the answer to both questions was, is, and ever shall be “no.” But that “no,” however kindly and compassionately it is offered, is not only spurned today; it can be a dangerous thing to say.

Ryan T. Anderson has every reason to know how dangerous it can be. The William E. Simon Senior Research Fellow at the Heritage Foundation and the editor of Public Discourse, Anderson (who has not seen this review before its publication) has long been at the forefront of the intense debate over same-sex marriage, both with and without co-authors. He has also been a leading participant in the debate over gender identity and transgender ideology, publishing many authors’ essays on the subject here in the past several years. And like the issue of same-sex marriage, the transgender debate stirs all sorts of passions about morality and justice, about identity and dignity, about the meaning of the law, and about the meaning of reality itself.

Also like the same-sex marriage debate—and in certain ways because of it—the transgender debate is moving rapidly in the direction of momentous changes in law and public policy, some of them brought about through dubious judicial readings of the Constitution and existing federal statutes, some of them through the ideological capture of bureaucracies in government and educational institutions. Once a case like James/Jan Morris’s was rare enough to be shrugged at by most people. But in the “transgender moment” in which we now live, a shrug just won’t do. The implications of widespread acceptance of transgender ideology are simply too great. Law, policy, and the practice of medicine are moving very quickly, with young children’s health and happiness often at the center of our concerns.

Start your day with Public Discourse

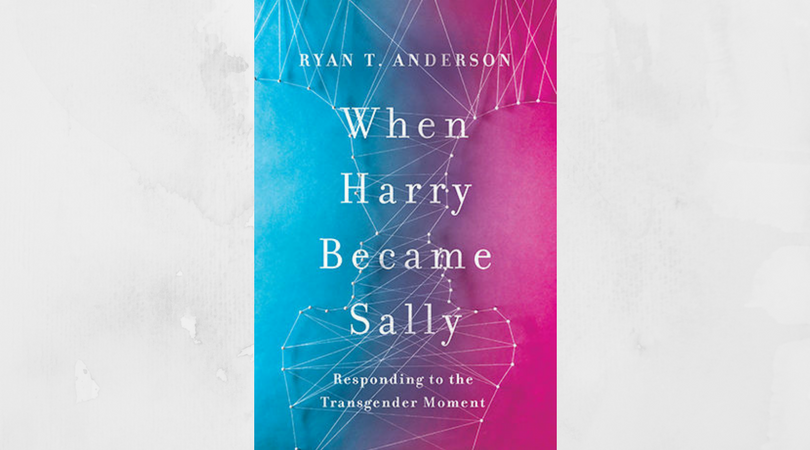

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.The time is right for a thorough look at our transgender moment in all its dimensions. What’s needed is a book that is dispassionate about what science tells us, passionate about getting law, public policy, and cultural norms right, with good sense and decency prevailing on every side, and compassionate toward those who suffer from gender dysphoria (and often from ill treatment by others). Anderson’s latest, When Harry Became Sally, is that book.

Dispassionate Science

After some opening vignettes of recent events showing the increasingly ideological and political dimensions of the transgender issue, Anderson turns to the arguments of transgender activists. For the most part, he gets out of the way and lets them speak for themselves, interjecting now and then only to raise questions or to observe contradictions and incoherence. And there is incoherence aplenty. They seem to be sure that “the real self is something other than the physical body.” But what can this “real self” possibly know about what it “feels like” to be the opposite sex? No one who is not a woman can know what it feels like to be one, and the same is true for the other sex. “The challenge for activists is to offer a plausible definition of gender and gender identity that is independent of bodily sex,” Anderson rightly observes. They can’t do it. As a consequence, they vibrate between assertions that are insupportable in themselves and incompatible with one another:

On the one hand, transgender activists want the authority of science as they make metaphysical claims, saying that science reveals gender identity to be innate and unchanging. On the other hand, they deny that biology is destiny, insisting that people are free to be who they want to be.

In spite of its self-contradictions, the movement’s bald assertions have gained a lot of ground. In late October 2017, in a case concerning transgender personnel in the military, Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly of the federal district court in Washington, DC opined, “Transgender individuals have immutable and distinguishing characteristics that make them a discernable [sic] class” for purposes of the Constitution’s equal protection principle. When military policy is remade on the basis of such a falsehood, ideology has infected the law in a bad way.

One of the many strengths of Anderson’s book is the skill with which he navigates not only the incoherence of the transgender movement’s activists, but also the sound science of what we know about sexual differentiation, about the condition known as gender dysphoria in adults and children, and about the effects of various medical interventions employed in “transitioning.” Anderson is particularly good on the scandal of the American Psychiatric Association’s redefinition of gender dysphoria—in the latest edition of its authoritative Diagnostic and Statistical Manual—from a disorder that inheres in the incongruence of biological sex and felt gender identity to one that is only considered manifest when the incongruence is accompanied by “significant distress or impairment” in a patient’s life activities. No new evidence led to this revision; it was purely a product of changed political views among the APA’s membership.

The fallout of this change has been a surge in “treatments” that a future generation will look back on with horror. With a dearth of clinical trials, the medical profession has undertaken “reassignments” that involve social and behavioral conditioning, hormone treatments, and surgical alteration of secondary sex characteristics. All of these remarkable intrusions have been made on the body for the sake of a dysphoria rooted entirely in the mind, with little to show for them: “The largest and most rigorous academic study on the results of hormonal and surgical transitioning . . . found strong evidence of poor psychological outcomes.”

The recent surge in medical interventions in the case of very young children is cause for the most intense concern. The best available evidence shows, in words Anderson quotes from Drs. Paul McHugh, Paul Hruz, and Lawrence Mayer, that “between 80 and 95 percent of children who say that they are transgender naturally come to accept their sex” and grow up normally as young men and women. Yet clinics are opening all over the country, with doctors ready to arrest young children’s puberty, put them on hormones characteristic of the opposite sex, and move toward surgery as early as is legally possible. Practitioners who recoil from such an automatic clinical approach to minor patients, like Dr. Kenneth Zucker in Toronto (who is not opposed to adult transitioning), are being hounded from the practice of their specialty. Some are fighting back, as in the case of the American College of Pediatricians, a professional association formed by doctors who dissent from the madness that is rapidly going mainstream. But it’s an uphill fight so far. Anderson has it right:

Children need our protection and guidance as they navigate the challenges of growing into adulthood. We need medical professionals willing to help them mature in harmony with their bodies, rather than deploy experimental treatments to refashion their bodies.

Passion for Justice and Decency

The transgender ideology, as every American knows who keeps up with the news, captured the policymakers of the Obama administration. The Departments of Health and Human Services, Defense, Housing and Urban Development, Education, and Justice all went to work in President Barack Obama’s second term to redefine “sex discrimination” to include “gender identity discrimination,” although neither the text nor the history of any federal law can justify such a reinterpretation. In the case I mentioned above involving transgender people in the military, a federal judge has already taken steps to give “gender identity” protected constitutional status.

But what would be—and in some places already has been—the consequence of such legal maneuvering? First of all, as Anderson observes, “Gender identity policies are not just about allowing citizens who identify as transgender to live as they choose, but about coercing the rest of us to go along with a radical ideology.” In some schools that have gone all in on this ideological project, parents are deliberately kept in the dark about what’s going on, even with their own children.

Moreover, the ideologues have forced the American people into a debate they never thought they’d be having, about who gets to use what bathroom. Serious privacy concerns, especially among girls and young women, are given the back of the hand by the transgender movement’s activists and their allied bureaucrats and policymakers. Even basic safety from voyeurism and sexual assault is at risk under the policies espoused by the activists. And fairness and justice to women is sacrificed by such harebrained ideas as letting young men “transitioning” to a female identity compete against young women in athletic competitions.

Anderson urges Congress to hold fast against the progress of transgender ideology in our legal system. Our national and state legislators certainly have the power to restore common sense to public policy. And now is a propitious time to act.

Compassion for the Suffering

The most affecting chapter in When Harry Became Sally is devoted to the personal stories of individuals who “detransitioned,” returning to identification with their biological sex after having previously identified with the opposite sex. The transgender movement’s response to such cases is either to pretend they don’t exist or to insist that these men and women were never really transgender in the first place. Of course, since doctors believed them when they said they were, and acted accordingly, these “not really” patients would have a pretty good case for accusing their former physicians of malpractice. And since declared feelings of being “born into the wrong body” are the only basis of a diagnosis that can lead from a change of wardrobe to the surgical excision of healthy sexual organs, no doctor can ever be sure that his patient will not one day wish to detransition. And what could he possibly do then to put things right?

These are truly awful tales of intense suffering. They are the personal stories of men and women, boys and girls, who went to medical professionals with terrible confusion and distress and received only harm where they sought relief. Now, in telling the truth about what happened to them, they attract the abuse and invective of the transgender movement’s ideologues. Some of them, understandably, prefer to tell their stories anonymously. All of them should be applauded for their courage and candor and thanked for their contribution to public understanding.

Anderson writes in his conclusion that these stories, more than anything else, led him to write When Harry Became Sally. “I couldn’t shake from my mind the stories of people who had detransitioned. They are heartbreaking. I had to do what I could to prevent more people from suffering the same way.”

I don’t know how it could have been done better, or by whom. Ryan Anderson has written the definitive book on this subject—ranging across medicine, psychology, culture, sociology, law, and public policy. He may have saved the minds and bodies—indeed, the very lives—of people he will never know. This “transgender moment,” this calamity of misdiagnosis, mistreatment, and injustice, can’t end a moment too soon. If ever there was a book that could call a halt to a catastrophe, this is it. May it be very widely read.