See the full symposium on Adam Bloom here.

In an eye-opening video produced last year by the Family Policy Institute of Washington, Joseph Blackholm interviews various students at the University of Washington on the justice of requiring “gender neutral” bathrooms, locker rooms, and showers. Through a series of deft questions, Blackholm cleverly highlights the unexamined, illogical assumptions that form the basis of the students’ positions. As he puts it,

It shouldn’t be hard to tell a 5’9” white guy that he’s not a 6’5” Chinese woman. But clearly it is. Why? What does that say about our culture? And what does that say about our ability to answer the questions that actually are difficult?

The video perfectly captures the soft, tolerant side of the dogmatic relativism that pervades the culture of higher education in America. But that softness also has a hidden potential to break into intolerant anger (see the hostile reaction to similar arguments by philosopher Rebecca Tuvel), threats of violence as occurred at the University of Missouri in 2015, or into actual violence, as recently occurred at UC Berkeley and Middlebury College. These events reflect a troubling pattern on college campuses and in our culture more generally.

Start your day with Public Discourse

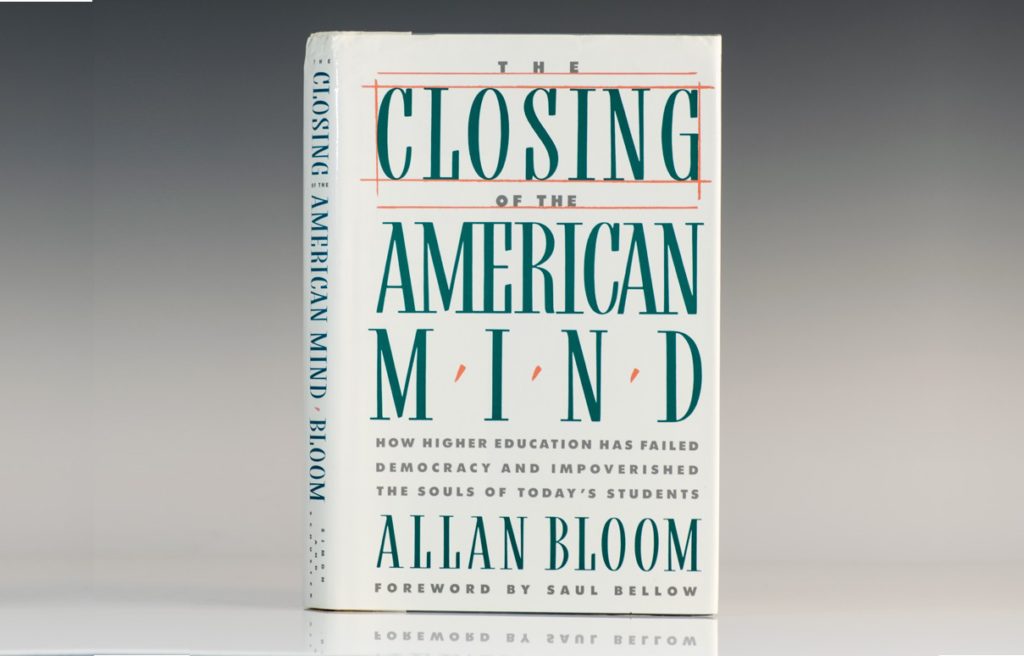

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.The defense of “snowflakes” by college administrators (as in this piece by Ulrich Baer, vice provost of New York University) is revealing, but if one wants to understand the real roots of this softness and violence, and the profound challenges they present to free government, there is no better guide than Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind: How Higher Education Has Failed Democracy and Impoverished the Souls of Today’s Students, published thirty years ago. In commemoration of this anniversary, Public Discourse is publishing a symposium treating each of the book’s three main sections.

Peter Lawler, one of America’s most insightful critics of popular culture, will treat Part One: Students, which includes some of Bloom’s most controversial arguments on subjects like rock music, the sexual revolution, feminism, and divorce. Michael Platt, author of an influential review of Closing and important essays on both Shakespeare and Nietzsche, will discuss Part Two: Nihilism, American Style. Paul Rahe will analyze Part Three: The University. Rahe, a distinguished intellectual historian, was a student of Bloom’s at Cornell University during the campus protests that Bloom narrates in this section. Those same protests caused Bloom to leave Cornell for the University of Toronto and Rahe to transfer to Yale University. Finally, Jon Fennell, accomplished philosopher of education, the driving force behind the establishment of the Classical Education program at Hillsdale College, and author of another early essay on Bloom and education, will write a summary and critique of the symposium.

In this essay, I offer some reasons why Closing is worthy of our attention, perhaps now even more than when it was first published.

All Is Not Well

Somewhat remarkably, this erudite book with a prosaic subtitle sold over a million copies and spent four months at the top of the New York Times Nonfiction Best Seller list. It also became something of a flash point between traditionalist conservatives and modern liberals in America’s culture wars. Yet both groups had a tendency to read into the book their own prejudices, leading them to misunderstand its basic argument. That argument defies the standard political narratives of the left or right, as did the author himself. Posthumous revelations of Bloom’s homosexuality and agnosticism do not undermine his defense of the Bible, the traditional family, or the study of Great Books. Rather, they reinforce one of the book’s main points: we are neither defined nor confined by our strongest desires, and reason can transcend both personal preferences and local prejudices.

Alternatively hopeful, pessimistic, provocative, and troubling, yet always brilliant, Closing has lost none of its power or its relevance. If anything, the crisis Bloom identified has only intensified, with the renaissance of angry and often violent protests on college campuses and in urban areas, the growing vitriol and vulgarity of political discourse, and the rise of nationalist movements here and abroad, which are increasingly skeptical of liberal democracy.

All is not well in America, or in the university, and Bloom offers a profound and compelling diagnosis of the common illness infecting them both. That illness involves the crisis of the West, which is fundamentally a crisis of reason—namely, the loss of confidence in reason’s ability to discover truth and guide human action. (Thus, Closing can be fruitfully read alongside works such as The Abolition of Man by C.S. Lewis, After Virtue by Alasdair MacIntyre, and Benedict XVI’s Regensburg Address).

A crisis of reason is also a crisis of liberal democracy, which depends upon reason to moderate competing theological and ideological claims. And a fortiori, this is especially a crisis of the United States, which Bloom calls “one of the highest and most extreme achievements of the rational quest for the good life according to nature.” “An openness that denies the special claim of reason,” Bloom writes, “bursts the mainspring keeping the mechanism of this regime in motion.” The loss of reason and nature as standards leaves people passionately “committed” to their “values” with no means to evaluate those values or negotiate their differences.

The Roots of Democracy—and of Violence and Repression

Always in the background of Bloom’s analysis is the fate of Weimar Germany. How did the most liberal of Western liberal democracies become transformed into a violent and repressive totalitarian regime? And why couldn’t the same thing happen to us?

For Bloom, this transformation was not simply the result of contingent historical events such as the Treaty of Versailles or the Great Depression. Its roots were planted long before, in the romantic reaction of philosophers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Friedrich Nietzsche to the “bougeoisification” (or what Nietzsche called “the borification”) of human beings under liberal democracy. Readers have noticed the similarities between Bloom’s description of his American students and Nietzsche’s description of the “last man” in Thus Spake Zarathustra, but they often miss Bloom’s greater concern: “Hitler proved to the satisfaction of most, if not all, that the last man is not the worst of all; and his example should have, although it has not, turned the political imagination away from experiments in that direction.”

In tracing the etiology of ideas that led to the crisis of the West, Bloom takes his reader on a whirlwind tour of the history of political philosophy. Aristotle, Plato, Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, Tocqueville, Marx, Freud, Weber, and Nietzsche (especially the first and the last on this list) feature prominently in a narrative that seeks to disclose the permanent questions of the human condition. These are questions about the relations between the passions and reason, the soul and the body, the individual and community, science and poetry, politics and philosophy, reason and revelation.

Rather than provide neat answers to these questions, however, Bloom invites his readers into genuine philosophical experience by making a convincing case for the competing positions. At times, this makes it difficult to tell whether Bloom is advocating a particular position or merely summarizing it. This has led to disagreements over whether Bloom’s ultimate sympathies rest with the classical Plato and Aristotle, the modern Machiavelli and Locke, or the postmodern Rousseau and Nietzsche.

However one comes down on this disagreement (and I think the evidence favors the first option), one cannot deny the singular capacity of Bloom’s style to entertain, enrich, and enlighten. Bloom’s prose, like poetry, has a luminous and suggestive quality that must be tasted, not paraphrased. This form reinforces the function of Closing. The problem is similar to that facing Socrates when he is arrested by Polemarchus in the opening scene of Plato’s Republic, a book Bloom translated and interpreted: What reasons can be offered to someone who denies the power of reason altogether? The answer for Bloom, as for Plato, is a philosophical poetry that elicits and feeds the natural human desire for wisdom.

The High Does Not Stand without the Low

Consider this example of Bloom’s style from Part Two:

A true political or social order requires the soul to be like a Gothic cathedral, with selfish stresses and strains helping to hold it up. Abstract moralism condemns certain keystones, removes them, and then blames both the nature of the stones and the structure when it collapses.

The soul as a Gothic cathedral is a striking image, making visible what is otherwise invisible. It effectively captures the elevation of soul one experiences on visiting a great Gothic cathedral such as Chartres or Notre Dame or Cologne—the sense of sacredness, solemnity, and transcendence. The simile also alludes to the subtle source of magic in the Gothic cathedral, its almost ironic combination of weight and verticality that is made possible by the arch-like flying buttresses supporting the walls. In the soul, as in the Gothic cathedral, “the high does not stand without the low,” to quote C.S. Lewis in The Four Loves. Who cannot detect, in the “abstract moralism” Bloom denounces, modern liberalism’s frustrated attempts to eliminate economic competition or root out gender differences?

The image provides a salutary reminder that human virtue is not simply natural but requires the artifice of education, which is at least as important and as difficult as the construction of a Gothic cathedral. No political regime (especially liberal democracy) can be indifferent to the virtue—and therefore the education— of its citizens.

The Danger of Indignation

I conclude by examining one final quotation, this time from Part Three. Bloom writes the following of the student protesters and their abettors in the sixties:

Indignation and rage was the vivid passion characterizing those in the grip of the new moral experience. Indignation may be a most noble passion and necessary for fighting wars and righting wrongs. But of all the experiences of the soul it is the most inimical to reason and hence to the university. Anger, to sustain itself, requires an unshakable conviction that one is right. Whether the student wrath against the professorial Agamemnons is authentically Achillean is open to question. But there is no doubt it was the banner under which they fought, the proof of belonging.

As it was in the sixties, so again today. Indignant anger has become a public passion. Yet Bloom shows how complex and problematic this passion is. Anger is distinctive to human beings (or rational beings), because it is not merely a physiological reaction to stimuli but is bound up with a judgment about right and wrong. But as Bloom points out, anger can also be the most irrational and destructive of passions, especially when it is directed toward perceived threats to oneself or one’s own. Bloom’s allusion to the central theme of Homer’s great epic the Iliad highlights this point: “Sing, goddess, the anger of Peleus’ son Achilleus / and its devastation.” Ordinary animals do not nurse wounded pride, slash at rivers that get in their way, or spend days relieving their anger on the maimed corpses of their enemies. Homer’s description is not far from the atrocities committed daily in parts of the Middle East. This may be our fate as well if we refuse the kind of moral education of anger that can only come from the recovery of reason.

Like a great book, The Closing of the American Mind sparks intense disagreements. Is Bloom’s description of the principles of the American Founding accurate? Does he caricature the flat souls of his students? Do philosophical ideas really have the power he attributes to them? Is his genealogy of ideas accurate? How does he understand the relationship between philosophy and morality? What does nature teach about the moral life? Can the restoration of a Great Books education in the university really be the remedy for the crisis of the West?

Whether or not Closing is itself a great book, it has the power to make the love and learning of great books attractive in the midst of America’s increasingly vulgar culture, and to restore the intimate connection between liberal education and liberty. For this alone, Bloom merits our profound attention, respect, and gratitude.