How unusual is Kermit Gosnell? That is the question that comes unbidden to mind when reading Gosnell: The Untold Story of America’s Most Prolific Serial Killer, a new book about the case of Dr. Gosnell, the abortionist who owned and operated the “Women’s Medical Society” abortion clinic at 3801 Lancaster Avenue in Philadelphia.

Gosnell’s charnel house of a clinic was raided in February 2010 on a well-founded suspicion that the doctor was running a “pill mill” selling illicit pain medication prescriptions. Following discovery of his horrifying abortion practice, Gosnell and others in his employ were indicted by a Philadelphia grand jury in 2011. In 2013, he was convicted on three counts of first-degree murder (for severing the spines of babies born alive), one count of involuntary manslaughter (for the death of a mother who died at his hands), and of other offenses under state law. He is now in prison for the rest of his life, without possibility of parole.

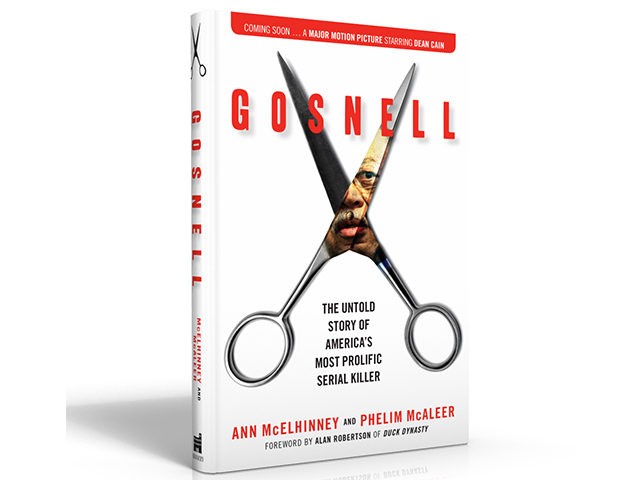

Authors Ann McElhinney and Phelim McAleer are Irish investigative journalists and filmmakers who have also produced a film about Gosnell that will be released later this year. They do not ask the question I asked above: how unusual is Kermit Gosnell? One could close this book with a final shudder, comforting oneself with the thought that Gosnell was an outlier, a freak on the fringes of the abortion trade. Thus one might put the frightful images of his crimes out of one’s mind more easily and think “well, that’s over, anyway.” But I’m not sure it should be that easy, because I am not sure Gosnell is really all that unusual.

How Many Gosnells?

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Yes, Gosnell specialized in late-term abortions, whereas the great majority are performed during the first trimester. But when the pro-abortion Alan Guttmacher Institute estimates that the number of abortions annually performed in the United States has only dropped below one million in the last five years, and when the Centers for Disease Control’s most recent statistics (for 2013) suggest that more than eight percent of them are performed after the first trimester, that is still somewhere in the neighborhood of 75,000 to 80,000 surgical abortions of unborn children with vital organs, beating hearts, and developing brains. Statistically “unusual” as such abortions may be, that is still a great many. At his busiest, Kermit Gosnell could not have done more than one twentieth of such abortions performed nationally.

Could we say that Gosnell was unusual because it seems that he only performed abortions after the first trimester? Perhaps so. But then there would be far more than twenty doctors and clinics doing at least some of these late abortions, and most of us would be barely aware of where they are happening. Then Gosnell would not be so very unusual in performing such abortions, only in doing them almost exclusively.

Was Gosnell unusual in running a clinic that was a filthy hellhole with roaming cats, untrained and unqualified staff, broken equipment, single-use instruments being reused, drugs being haphazardly administered, and the remains of aborted fetuses stored everywhere—babies in freezers, severed feet in jars like bizarre keepsakes? This may well have been the foulest, most unsanitary and unsafe abortion clinic in the United States. So yes, one might want to stipulate that Gosnell was an outlier, running a clinic so vile that surely—surely—there can’t be another as bad as that anywhere else.

And yet . . .

How did Kermit Gosnell manage to operate for decades, never investigated, never shut down, never even fined by Pennsylvania authorities for his many breaches of ordinary standards of care, let alone prosecuted for the outright crimes he committed?

It was not because he was especially careful or clever. As McElhinney and McAleer know from having interviewed him in prison, Gosnell is a man with an inflated sense of his own intelligence and accomplishments, a narcissist who continues to believe that he was wronged, that he will one day be vindicated because all he did was devote himself to the “vocation” of helping poor women eliminate their unwanted unborn children. He never took any particular steps to conceal his conduct from the authorities. Indeed, when his clinic was raided by the authorities who got wind of his illicit prescription sideline, Gosnell coolly informed them that he would be right with them as soon as he performed one more abortion.

More incredibly still, after consulting with both the state Department of Health and the FBI, the law enforcement officers on the scene permitted Gosnell to perform that abortion, even while they could look about them and see filth, squalor, misery, and body parts. This is the moment, still early in the authors’ tale, when one begins to see how powerful is the grip of the abortion ideology that manufactured a “constitutional right” and has defended it for the last forty-four years.

And thus the suspicion is planted. If this butcher could carry on virtually in the open for so many years—if he could even be permitted one more “procedure” before police on the scene put an end to his sordid business—then how many other clinics operating essentially like his are there in our country?

The Legal Status of Late-Term Abortion

Repeatedly over the years, authorities turned a blind eye, even when women were hospitalized after a visit to Gosnell’s clinic—even after two of them died following abortions there. When the drug raid brought his abortion practice to light, police and prosecutors learned that he had routinely ignored virtually every provision of the state’s abortion law.

Even then, what it took for prosecutors to act was the discovery that on probably hundreds of occasions Gosnell had induced live births rather than killing the unborn in utero as a legal abortion requires, and then finished his bloody work by “snipping” the babies’ spinal cords at the neck with a pair of surgical scissors. These deaths prompted the charges that sent Gosnell away for the rest of his natural life. They were not abortions; they were post-natal murders, and they are the reason the authors refer to him as “America’s most prolific serial killer.”

But wait. These deaths are supposed to be illegal to bring about even in utero, let alone ex utero, aren’t they? McElhinney and McAleer refer repeatedly to the provision of Pennsylvania law that prohibits any abortion at twenty-four or more weeks’ gestation. The only exceptions in state law are when a doctor “reasonably believes that it is necessary to prevent either the death of the pregnant woman or the substantial and irreversible impairment of a major bodily function of the woman.” And in such exceptional cases, other requirements kick in, such as the presence of a second physician, the performance of the abortion in a hospital, and so on.

This law was written to push back against the Supreme Court’s holding in Doe v. Bolton, the 1973 companion case to Roe v. Wade. In Roe, Justice Harry Blackmun said for the Court that it was permissible for states to prohibit post-viability abortions, “except where it is necessary, in appropriate medical judgment, for the preservation of the life or health of the mother.” But in its decision the same day in Doe, the “exception” made in Roe was so expanded as to swallow up the rule and make prohibition of any abortion virtually impossible. There Blackmun wrote that the “medical judgment” that a post-viability abortion is “necessary” could legitimately take into account “all factors—physical, emotional, psychological, familial, and the woman’s age—relevant to the well-being of the patient.” In other words, if a doctor is willing to do it for any reason a woman gives—for what reason could not be gathered into the emotional, psychological, or familial factors?—then the abortion cannot be prohibited, regardless of the gestational age or viability of the unborn child.

The little-appreciated Doe expansion of Roe’s “exception” language is why pro-lifers can truthfully say (though it is denied by abortion advocates) that since 1973 the effective law of the land has been “abortion on demand throughout pregnancy.” And this is what Pennsylvania challenged in the late 1980s, if only at the margins, with its much tighter health exception for abortions after twenty-four weeks.

That law also included other restrictions on access, such as spousal notification or a twenty-four-hour waiting period, that were challenged in the litigation that resulted in the Supreme Court’s 1992 ruling in Planned Parenthood v. Casey. But the post-twenty-four-week ban, with its tight life-or-health exception, was not challenged by abortion advocates. Why didn’t they challenge the late-term prohibition along with the less onerous restrictions? Did they believe that it would simply be ignored as a dead letter, by virtue of the standards set forth in Doe? Or did they fear that if challenged, it might be upheld by a Supreme Court that was viewed at the time (thanks to recent Reagan and Bush appointments) as poised perhaps to overturn Roe itself, which the United States, as friend of the Court, was urging it to do?

In retrospect, there is reason to believe that both of these explanations have merit. For what happened in Pennsylvania is that, with Roe reaffirmed by Casey, the late-term abortion ban stayed on the books but went unenforced, and Gosnell was the beneficiary of the neglect. Complaints, injuries, hospitalizations, even deaths caused by his practice should have long ago brought his activities to the attention of police and health authorities. In the medical community in and around Philadelphia, Gosnell’s specialty in very late-term abortions appears to have been well-known, but doctors were unwilling to talk to police about him, even after he was shut down. And the national media reflexively went into virtual blackout mode on the Gosnell case—until goaded into paying a little attention to his trial by the liberal pro-life columnist Kirsten Powers. Since his conviction, media darkness has descended again.

Why? Why did those who could have stopped him look away? Why did the police raiding his clinic permit him to perform one more abortion in the next room while they waited to interview him? Why did the media treat his trial like it was radioactive? Could it be because they really have imbibed the idea, from our Supreme Court, that any abortion carried out by any physician on any woman at any stage of her pregnancy is absolutely shielded from the ordinary processes of law by the Constitution itself? Some may have found this state of things appalling but felt helpless to act against it. Others may have felt that stopping Gosnell would come at too high a cost to the status quo.

Either way, the result was that public authorities allowed Dr. Kermit Gosnell to carry on his bloody trade for years, so incompetent and uncaring in his practice that he apparently preferred delivering late-term babies and murdering them to aborting them in utero.

But is Pennsylvania unique in this self-inflicted blindness? I end where I began. How many other abortionists elsewhere—in cleaner clinics, perhaps—are today doing much the same as Gosnell did? Read this harrowing book, and you will wonder too. Don’t for a moment think the answer is “none.”