It was nearly five years ago that I first received data back from the research firm that had carried out the New Family Structures Study (NFSS) protocol. Shortly thereafter, I began to question the scholarly consensus that there were “no differences” between same-sex and opposite-sex households with children. My skepticism didn’t sit well with the guild.

Social network analysts subsequently assessed patterns of “citation networks” in the same-sex parenting literature and concluded that there is indeed a consensus out there that claims there are “no differences.” I see it. I just think the foundation for the consensus is more slipshod than rock-solid. It is the result of early but methodologically limited evaluations that formed a politically expedient narrative. It is not the product of many rigorous, sustained examinations of high-quality data over time, across countries, and using different measurement strategies and analytic approaches.

Some liken the debate over the science of same-sex parenting to that around climate change. They argue that the science is so extensive, the published studies so numerous, and the conclusions so overwhelmingly unidirectional that only scientists acting in bad faith would object. But that’s not where this field of study is. How can we possibly come to a legitimate consensus about the short and long-term effects of a practice (childrearing) of a tiny minority about whom generalizable data of sufficient size for valid comparative analysis was not available until the past decade? The answer, of course, is that you cannot—or rather should not—yet.

What we have, rather, is a politicized consensus generated by lots of small studies of tiny, non-representative samples misinterpreted as applying to the entire population of same-sex parents. It is—by comparison to climate change—like saying that since the surface temperatures in Taiwan, Togo, and Texas have inched up a degree or two that the entire globe must have as well. Scientists know better than to declare such a thing based on limited evidence.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.In fact, I am unaware of any other domain of science in which scholars have so little high-quality data to answer comparatively new research questions and yet are so quick to declare those questions answered and done with. We don’t do that in any other field or with any other question. What ought to be an empirical matter—an important one, no doubt—has instead turned into a moral test of fealty.

Where’s the Data?

A popular misreading of that analysis of citation networks is that there are over 19,000 quality studies of same-sex households with children, and that not one of them has detected problems. The authors themselves note that is not the case. Their study began with what amounts to over 19,000 scholarly “hits” on an online Boolean word search. That is, there were 19,000 publications on the ISI Web of Science that used the word “gay” or “lesbian” or “homosexual” or “same-sex” and “parent” somewhere in the title or abstract. Far fewer were actually assessed in their analysis (as they pointed out). Indeed, anyone who pays careful attention to this domain knows that there aren’t nearly as many studies as is commonly believed—indeed, well under 100 that are worth discussing—and fewer than ten datasets that can appropriately yield generalizable information about the population of same-sex households with children.

If I were up against 19,000 quality studies that disagreed with me, I would have long ago gladly capitulated. But that’s not the scientific reality. Instead, two datasets—each of which has significant problems here—are responsible for the majority of studies upon which this “consensus” is based.

First, twenty-six peer-reviewed studies have emerged from just one data source: the National Longitudinal Lesbian Family Study. It repeatedly surveyed seventy-eight children of mostly white, educated, well-off lesbians who were recruited to participate. It may not be a stretch to suggest that these are the seventy-eight most influential children in modern American social and legal history. For nearly twenty-five years now, the scholarly community (and the media) has been treated to studies of this unique cluster of kids, and the general public has been left with the impression that they represent the whole population of children of American lesbian mothers. Moreover, it stretches the imagination to suggest that these seventy-eight respondents, now followed for nearly twenty-eight years, are still valid, reliable sources of information. When the adolescent children of lesbian parents are being intermittently interviewed for a study whose results have proven quite politically expedient—and almost always covered favorably by the mainstream media—it is prudent for scholars to be skeptical.

Second, the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) yielded forty-four cases of respondents with same-sex parents and has been featured in dozens of peer-reviewed publications. Analysts commonly created “matched” datasets of the children of heterosexual single parents or stepfamilies for use in comparisons. (How exactly they created these often remained under-explained.) Concern has mounted, however, that as many as twenty-seven of the forty-four cases may be dubious. I recognize (and admitted) that a small number of the 248 NFSS cases in which a respondent reported that a parent had had a same-sex relationship were questionable and could profitably be discarded (without effect, even). The same, on a much larger scale, has happened to US and Canadian Census data. In other words, this is difficult territory to measure accurately, and errors happen in spite of efforts to minimize them. Not exactly what you would expect in a domain characterized as displaying a clear consensus.

As much as it may seem convenient to make the comparison with climate change, it is simply not commensurate. I am no physical scientist, but I know that there are thousands of geologists and meteorologists who have collected and evaluated data on climate change. Federal, international, and nonpartisan organizations alike are interested in understanding what’s going on with the weather. By contrast, there are perhaps thirty social scientists who are primarily responsible for the “consensus” on the benefits of same-sex parenting. And less than half of those reappear with regularity as authors of studies that tend to use and recycle old data.

How Does the “No Differences” Story Work?

So how exactly does the consensus narrative work? How does it continue to enjoy popular legitimacy? The story of “no differences” between same-sex and opposite-sex households with children is characterized by four repetitive themes in the published research. They are:

1. Small samples are commonly prone to declarations of no statistically significant differences, due to limited statistical power to detect such.

When you’re comparing seventy-eight cases or forty-four cases, you cannot easily discern whether between-group differences that appear at face value are actually statistically different from a null finding. Hence it is easy to declare in favor of the null hypotheses—that you found no differences. Technically. This is typically followed by a dutiful “caution” saying something like “modest statistical power to detect differences.” Mission accomplished.

2. While differences are often apparent prima facie, once you “control for” (or set aside) sexual minorities’ greater household instability, it is easy to conclude that the sexual orientation of parents does not directly cause problems. But this means that indirect effects—the pathways via which most suboptimal child outcomes happen—are ignored.

This common pattern characterizes nearly all analyses of high-quality datasets since 2010. Unsurprisingly, it recently reappeared in a new study of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study—Kindergarten cohort published in the Journal of Family Issues. This move is obvious even from the abstract: “Results indicate that nontraditional family structures are associated with poorer psychosocial well-being, but this is largely accounted for by changes and transitions experienced in the creation of new families.”

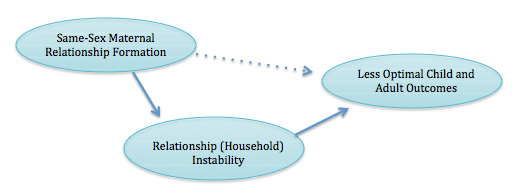

This approach assures that scholars treat household upheaval and parental romantic decisions as independent phenomena, unrelated to each other and to sexual orientation. Kansas State University professor Walter Schumm, after testing for indirect effects on child outcomes in the NFSS, concluded that “It is one thing to say a direct effect was not significant but another entirely to say that (household) structure did not matter . . .” That’s because household structures can often indirectly foster poorer (or better) outcomes. That makes sense, because social reality is best thought of in terms of a complex process among interrelated influences, rather than a snapshot in time of independent factors that have nothing to do with each other. The “consensus” leans on the latter approach.

The conceptual model above depicts such a process, signaling a plausible weak or even null direct effect of same-sex maternal relationship formation on child outcomes, but a strong indirect one—via its effect on household “transitions.” That is, an elevated break-up rate of female same-sex couples is a key mechanism here. (The story is not about sexual orientation effects but about the effects of consolidating gender preferences. The same explains the “open” relationship pattern among gay male couples.) I understand the impulse to ignore patterned instability out of a desire not to appear mean. But just know that we have moved well afield of science at that point.

3. Where differences remain, they are apt to be in psychosocial outcomes for which blame is typically leveled at the respondents’ social context (discrimination) rather than what may be going on in their household.

This simply means that where differences do not disappear after controls for instability, most interpreters chalk them up to a hostile social environment confronting the parents and/or the children. Recent analyses—including the NFSS, the National Health Information Study, and the New Atlantis comprehensive report on sexuality and gender—all document the corrosive effects of stigma and discrimination. And yet stigma and discrimination do not explain why differences remain.

4. The children of gay or lesbian single and stepparents appear, on average, to fare comparably to those of straight single and stepparent counterparts. Hence there tend to be “no differences” across types of solitary, fractured, and reconstituted households.

This approach featured prominently in a variety of studies intended to generate an “apples vs. apples” type of comparison. Since it is impossible for two mothers or two fathers to both participate in the conception of a child—one cannot but be a stepparent—it made sense to researchers to altogether drop the children of biological parents from the analysis.

I understand the logic. It’s the popular interpretation of this move that is deceptive. When media consumers read “no differences,” they presume it means no differences in general. But what it really means is no differences among gay and straight single-parent and step-parent families. It’s a subtle but very important distinction. Indeed, I cannot think of any population-based dataset where the children of stably married mothers and fathers appear the same as any form of step-parenting, single parenting, or adoptive households. You can make them look comparable, however, by employing any of these four strategies listed above.

Children Need Both Mothers and Fathers

At bottom the question remains: what is best for children? The answer to that question has not changed. The children of the world do not want liquid love. They want the solid, stable presence of a mother and a father, preferably their mother and their father. It’s not always possible, I realize, but let’s not pretend it doesn’t matter.

Behind the rhetoric about “diverse composition” of households, “evolving notions” of family, and the “transitional experiences” so common to same-sex households are real children who love their mothers (and fathers) but loathe the upheaval to which they are commonly subject. It reminds me of a story recently told to me by a professor from another university, who lives next door to a woman—a mother—who’s been through three same-sex relationships in the past few years that they’ve been neighbors. The professor confessed that he’ll be out in his back yard playing with his kids, only to notice his neighbor’s son looking at them over the fence, watching, wanting. The boy’s mother, aware of this, lamented to the professor, “I’m doing the best I can.”

Explaining control variables and indirect effects to the boy would be small comfort, I suspect. He wants a father—and he deserves one.