Can conservatives learn anything from a New York Democrat who opposed Reaganomics, consistently voted for Medicaid to fund abortions, opposed welfare reform in the 1990s, and helped launch the independent political career of one Hillary Rodham Clinton?

In a word: yes.

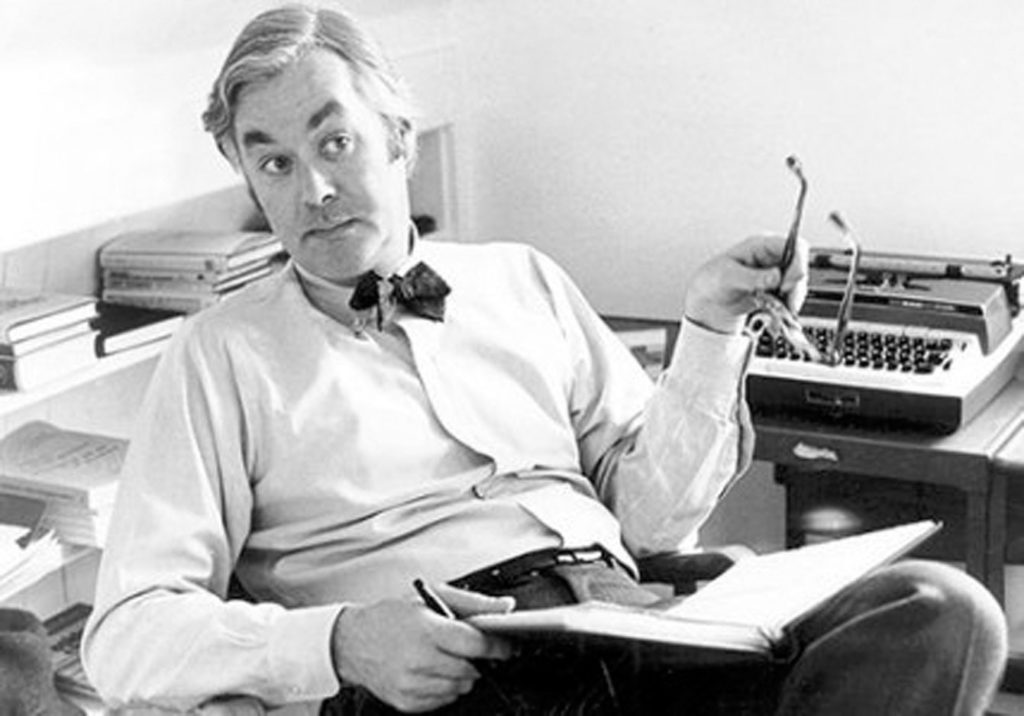

The Democrat in question is the late White House counselor, ambassador, scholar, and senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan. Moynihan’s career included service in two Democratic and two Republican administrations, as well as four terms as US senator for New York. His contested legacy in public service offers practical lessons for those engaged in politics and wisdom for us—blessed or cursed as we are to live in what political philosopher Jean Bethke Elshstain called “interesting times.” Understanding this statesman’s contributions to American politics is essential for understanding the mid late-twentieth century and our own troubled moment.

Moynihan displayed the less-praiseworthy traits associated with politicians—ambition, flattery, and attraction to power—and took policy positions with which most conservatives would disagree, but he also exhibited three political virtues that all political leaders should emulate: industriousness, courage, and wisdom.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Industriousness

Moynihan had progressive goals in the definitional sense: he wanted Americans, particularly the poor and vulnerable, to make progress. He wanted to see greater equality of opportunity and ultimately of condition for all Americans. He worked tirelessly to find concrete ways of achieving these goals.

Take one of his less-celebrated, if less-maligned, contributions to American public life, reported in Godfrey Hodgson’s biography: traffic safety. In 1959, he published a long-form article in The Reporter (edited by Irving Kristol), urging the institution of federal safety standards for automobile manufacturing. Drawing from the work of public health expert Dr. Michael Haddon, Jr., he framed the “disastrous epidemic” of deadly traffic collisions—which would soon become the leading cause of death for Americans under forty-four—as a public health issue. He identified the problem, explained why the federal government was the only instrument that could make a difference, and forcefully argued for public action. Thanks to further research and advocacy by Ralph Nader, which elicited unpopular intimidation from General Motors, Congress passed and Lyndon B. Johnson signed the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966.

Moynihan approached “the social field” with the same level of energy and the goal of improving life in concrete terms. The Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act was minor compared to the flood of legislation accompanying the Great Society and the War on Poverty. Though he was later critical of many Great Society programs, Moynihan’s ideas contributed to the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 and, more controversially, to LBJ’s June 1965 commencement speech at Howard University. That speech, perhaps representing the apogee of postwar liberalism, connected the War on Poverty with what LBJ called “the next and the more profound stage of the battle for civil rights” for black Americans.

“The Negro Family: The Case for National Action,” more commonly known as the Moynihan Report, provoked accusations of racism when it was leaked in August 1965, the same month that LBJ signed the Voting Rights Act and that the Watts riots erupted. Moynihan called for a “national effort” to attack what he saw as the primary barrier to the well-being of black Americans in urban ghettos: a rapidly deteriorating family structure resulting from the legacy of slavery and the epidemic of unemployment. Left unchecked, Moynihan argued, this “tangle of pathology” would be self-perpetuating, leading to a spiral of social disorganization. His goal was to “break into [the] cycle” of family instability, low educational performance, and unemployment, providing the means for black Americans to attain equality—“not just equality as a right and a theory but equality as a fact and equality as a result,” as LBJ put it. The “national effort” Moynihan proposed to coordinate welfare and jobs programs in a way that supported family stability was not the last of the bold federal initiatives he championed to advance social progress. So why did he face vociferous attacks from the left?

Courage

In addition to industriousness, Moynihan had intellectual and political courage. In 1965, even as civil rights activists and political leaders had bulldozed legal and political barriers for black Americans, Moynihan saw the “harsh fact” that another, more complex and self-perpetuating barrier would, along with continued discrimination, obstruct the liberal goal of bringing black Americans, particularly in urban ghettos, to “full and equal sharing in the responsibilities and rewards of citizenship”: deteriorating family structure. Facing hard facts, particularly associated with the “new crisis of race relations,” and trying to deal with them exposed Moynihan to unfounded charges of racism throughout his career. He bristled, but continued to point out “unseasonable, unpalatable truths.” At an uncertain point in his career, between service in the Johnson and Nixon administrations, he also had the courage to chide fellow liberals for failing to do so. As he himself mused, perhaps somewhat bitterly, “social scientists worthy of the name will call ’em as they see ’em, and this can produce no end of outrage at the plate, or in the stands.”

Wisdom

In his 2015 book American Burke, Greg Weiner identifies a “politics of limitation” as the core of Moynihan’s wisdom. Like the neoconservatives with whom he associated, Moynihan understood the complexity of social systems. Most social problems, particularly in cases of severe dysfunction, cannot be solved with the wave of a legislative wand.

Having seen that the extensive network of Great Society services and programs was incapable of unraveling the tangles of pathology associated with poverty—though they benefited middle class social workers—Moynihan championed a more direct means of alleviating poverty: give money to poor families. Notice the scheme’s title: Family Assistance Plan. The FAP would only cover families with children, unlike the Universal Basic Income currently under discussion. He stressed this element in his public advocacy: “Welfare reform is about families. It’s about keeping families together.”

Moynihan’s focus on the family as the basic, determinative social unit was grounded in personal experience and empirical evidence, but also in a philosophical conviction about the necessity of “private subsystems of authority” for the functioning of a liberal society. He proffered a liberal defense of the Catholic principle of subsidiarity and saw federalism as “a fundamental expression of the American idea of covenant.”

An Unfinished Career: Moynihan’s Relevance

Due to the vicissitudes of politics and social trends against which both conservatives and traditional liberals seem powerless, Moynihan was unable to accomplish much of what he set out do to in terms of legislation. In many ways, his was an unfinished career, and his legacy of “uncommon liberalism” awaits a baton-carrier.

On the right, the rising scholar-Senator Ben Sasse of Nebraska has appealed directly to Moynihan’s legacy of empiricism and promoted civil society’s intermediary institutions as central to “The American Idea.” Similarly, reform conservatives like Yuval Levin embrace decentralization and subsidiarity and focus on solving concrete public problems. But what would especially serve this country will be difficult for the fractious conservative movement to furnish: liberals who will take up Moynihan’s baton.

Liberal columnist E.J. Dionne agrees that we need more Burkean liberals and conservatives. He critiques the conservative movement, blaming the Tea Party for what he sees as a radical individualism that has become anti-government and anti-community. British conservative philosopher Roger Scruton likewise argues that conservatives need to “[defend] government as an expression in symbolic and authoritative forms of our deep accountability to each other.”

But liberals also need to reclaim a realistic and limited vision of government. As Weiner argues, “government [has] to appreciate what it [cannot] do in order to undertake successfully what it [can].” Moynihan understood that government could essentially regulate and redistribute resources, not micromanage social and economic life. Both Scruton and Moynihan argue that government should empower people rather than making them dependent so that, in Scruton’s words, “citizens’ initiatives … take the lead.” Moynihan championed not only the preservation of tax exemptions, but the expansion of tax deductions for families to send their children to private and parochial schools, on the liberal grounds that this would most benefit poor and working-class Americans. Would this be imaginable for a liberal today? If influential wings of the conservative movement have indulged in anti-government rhetoric, influential wings of liberalism (or progressivism) have become anti-society. The statists are gaining traction over the pluralists.

A humane and noble form of liberalism seeks to ease suffering, expand opportunity, and protect the vulnerable from exploitation. These are worthy pursuits and legitimate functions of government, though they must be balanced with the preservation of ordered liberty—and recognition of government’s limitations in confronting complex social problems. Scruton writes, “conservatism should be a defense of government against its abuse by liberals.” So much the better if Burkean liberals like Moynihan will join in this effort.

Moynihan was not so much a soothsayer as a diligent student of trends with a knack for identifying important facts. This ability to recognize important facts, the stubborn ones that will shape social and political reality for decades, is indispensable for leaders in our time, drowning as we are in a deluge of information. Some of the facts and trends he identified remain with us, notably the continuing crisis of race relations. Whatever the merits of Moynihan’s recommendation to President Nixon for a period of “benign neglect” in racial matters, this is impossible in the post-Ferguson political climate. Though W. Bradford Wilcox and Nicholas H. Wolfinger remind us of the good news that the majority of black Americans, including black men, have made substantial economic and social progress since Moynihan’s warnings, sociologist Orlando Patterson explains that a “problem minority” of “disconnected youth” fuels American inner cities’ social and economic problems.

The crisis of race relations and dysfunctional inner cities is an epiphenomenon of the most critical long-term issue facing American political and civic leaders: “the crisis of social disorganization.” It is most critical because it is connected to other social problems, from drug abuse to suicide rates to crime. It also forces Americans to confront the “liberal dilemma” that our society’s most critical needs are precisely in the areas where government can do the least. The liberal dilemma derives from Moynihan’s “conservative truth” that “it is culture, not politics, that determines the success of a society.”

Even if Moynihan’s “liberal truth” is right—that “politics can change a culture and save it from itself,” it is not clear that politics can restore a crumbling and fracturing culture. As Moynihan told a crop of Notre Dame graduates in 1969, “government cannot cope with the crisis in values … sweeping the Western world.”

If conservatives readily intuit Moynihan’s wisdom, we should also learn from his industriousness and courageous optimism. His recognition of the limits of governmental programs was never an excuse for inaction. What’s more, he pointed the way toward a political vision conservatives should embrace: a pathway between laissez-faire and statism built on revitalized non-governmental institutions—family, church, neighborhood, union—that can “mediate between the individual and the state.” In this political vision, federal and state governments act as unifying “instrument[s] of common purpose,” but always in the service of a vibrant civil society.

Given the degree of cultural and political fragmentation in our country today, Moynihan’s pathway of diverse intermediary institutions and Burkean “little platoons” is perhaps the only means of preserving and renewing the republic, which depends on functioning social institutions to survive. We must hope with Weiner that Moynihan is not the last of the Burkean liberals, and that Burkean liberals and conservatives can work together to find a way forward. The effort will demand uncommon industriousness, courage, and wisdom from our political and civic leaders in these interesting times.